Genre 101 is a series that looks at the past and present of a game genre to find lessons about what defines it. This time, “guest lecturer” Lucas White gives us a primer on the beat-’em-up.

A new path for combat

Lucas White: Before Kung-Fu Master, combat games were generally one-on-one affairs. Kung-Fu Master bears a rudimentary resemblance to later, more refined games, as the player navigates down linear paths, punching and kicking endlessly spawning enemies before reaching the boss fights. This basic formula would lead to Renegade and later Double Dragon. The familiar street brawling setting trope came into play, and players were given more combat options, such as the use of items and vertical movement.

Lucas White: Before Kung-Fu Master, combat games were generally one-on-one affairs. Kung-Fu Master bears a rudimentary resemblance to later, more refined games, as the player navigates down linear paths, punching and kicking endlessly spawning enemies before reaching the boss fights. This basic formula would lead to Renegade and later Double Dragon. The familiar street brawling setting trope came into play, and players were given more combat options, such as the use of items and vertical movement.

Graham Russell: It’s important to realize the genre’s roots are very much tied to martial arts films. The genre swelled in popularity around this time, and largely revolved around one super-talented fighter taking on waves and waves of enemies. Sound familiar? While we saw some branching out later, much of the brawler’s first decade followed this formula.

Graham Russell: It’s important to realize the genre’s roots are very much tied to martial arts films. The genre swelled in popularity around this time, and largely revolved around one super-talented fighter taking on waves and waves of enemies. Sound familiar? While we saw some branching out later, much of the brawler’s first decade followed this formula.

Yeah! Kung-Fu Master itself is supposedly based on Jackie Chan’s Wheels on Meals and Bruce Lee’s Game of Death, so anyone interested should watch those after playing Kung-Fu Master to see how movie to video game adaptations worked out in the ’80s. There were also several games based on those martial artists outright, instead of having a tie to a specific film.

Yeah! Kung-Fu Master itself is supposedly based on Jackie Chan’s Wheels on Meals and Bruce Lee’s Game of Death, so anyone interested should watch those after playing Kung-Fu Master to see how movie to video game adaptations worked out in the ’80s. There were also several games based on those martial artists outright, instead of having a tie to a specific film.

Brawlers get a boost

River City Ransom is part of the same series of games as Renegade, known as Kunio-kun in Japan. RCR was a fairly typical brawler mechanically, but it took place in a larger, connected world and introduced RPG elements, most notably various shops in which you could buy food to permanently boost your stats. This exact formula would later return in Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, but character customization would appear in various forms across the genre after RCR.

River City Ransom is part of the same series of games as Renegade, known as Kunio-kun in Japan. RCR was a fairly typical brawler mechanically, but it took place in a larger, connected world and introduced RPG elements, most notably various shops in which you could buy food to permanently boost your stats. This exact formula would later return in Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, but character customization would appear in various forms across the genre after RCR.

Technos made much of the beat-’em-up genre, with two separate franchises, but it also managed to create myriad hybrid designs. Want beat-’em-up soccer? Beat-’em-up dodgeball? As it turns out, adding a bit of brawling to sports works beautifully. But do you think the pure form is best?

Technos made much of the beat-’em-up genre, with two separate franchises, but it also managed to create myriad hybrid designs. Want beat-’em-up soccer? Beat-’em-up dodgeball? As it turns out, adding a bit of brawling to sports works beautifully. But do you think the pure form is best?

The pure form works best as far as mass appeal is concerned. The sports games are great, and I’m pleasantly shocked to see that we got a few of the newer ones in North America. Unfortunately, they fall pretty hard into niche territory for several reasons. The traditional brawlers also have nostalgic value, while the other Kunio-kun games were obscure from day one over here.

The pure form works best as far as mass appeal is concerned. The sports games are great, and I’m pleasantly shocked to see that we got a few of the newer ones in North America. Unfortunately, they fall pretty hard into niche territory for several reasons. The traditional brawlers also have nostalgic value, while the other Kunio-kun games were obscure from day one over here.

Fighting fantasy

Golden Axe represented a split in the genre in terms of common settings, shifting the formula from urban street fighting to high fantasy combat. Golden Axe brought screen-clearing magic abilities into the fray, which would lead into games like Capcom’s Dungeons & Dragons series and Vanillaware’s Dragon’s Crown.

Golden Axe represented a split in the genre in terms of common settings, shifting the formula from urban street fighting to high fantasy combat. Golden Axe brought screen-clearing magic abilities into the fray, which would lead into games like Capcom’s Dungeons & Dragons series and Vanillaware’s Dragon’s Crown.

I think the biggest change that came with the setting shift was a focus on loot. Golden Axe only had a little bit, like potion pick-ups, but infusing the D&D inventory-driven tradition gave beat-’em-ups one more addictive element.

I think the biggest change that came with the setting shift was a focus on loot. Golden Axe only had a little bit, like potion pick-ups, but infusing the D&D inventory-driven tradition gave beat-’em-ups one more addictive element.

Right! You could also argue that dungeon crawlers such as Diablo or Baldur’s Gate (especially the console versions) have their roots here, and loot is a big factor in those as well.

Right! You could also argue that dungeon crawlers such as Diablo or Baldur’s Gate (especially the console versions) have their roots here, and loot is a big factor in those as well.

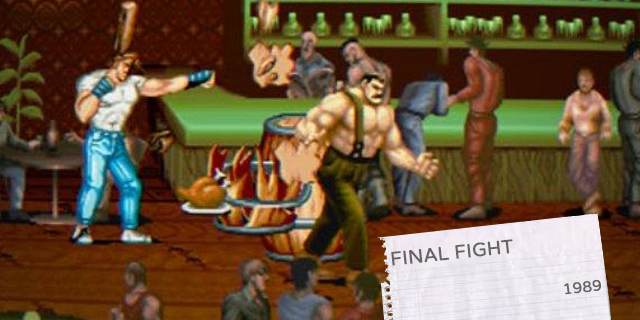

Grappling with new mechanics

Final Fight is interesting to me for two reasons. One: it was originally supposed to be a sequel to the original Street Fighter. That ended up not working out for obvious reasons, but the Final Fight series was still incorporated into the Street Fighter canon. This led to the idea of simpler titles (such as brawlers!) being a fun way to expand the universe of a larger, flagship series by way of spinoffs. A good modern example of this: Metal Gear Rising. Two: Mike Haggar, one of the playable characters, could use wrestling moves in addition to the usual punch, kick and special health-sapping technique. This was another expansion of player options, and would go even further in Golden Axe: The Revenge of Death Adder. All four players could grab an enemy and perform a group wrestling maneuver.

Final Fight is interesting to me for two reasons. One: it was originally supposed to be a sequel to the original Street Fighter. That ended up not working out for obvious reasons, but the Final Fight series was still incorporated into the Street Fighter canon. This led to the idea of simpler titles (such as brawlers!) being a fun way to expand the universe of a larger, flagship series by way of spinoffs. A good modern example of this: Metal Gear Rising. Two: Mike Haggar, one of the playable characters, could use wrestling moves in addition to the usual punch, kick and special health-sapping technique. This was another expansion of player options, and would go even further in Golden Axe: The Revenge of Death Adder. All four players could grab an enemy and perform a group wrestling maneuver.

Oh man, Revenge of Death Adder is great. What do you think the addition of grappling moves did to beat-’em-up combat? How does that change the strategy? Certainly, before they were added, mostly there wasn’t much of a strategy at all.

Oh man, Revenge of Death Adder is great. What do you think the addition of grappling moves did to beat-’em-up combat? How does that change the strategy? Certainly, before they were added, mostly there wasn’t much of a strategy at all.

There’s a degree of risk involved. The grappling moves are flashier and stronger, but they often require you to literally walk into your enemies to grab them, and leave you wide open to other attacks. I’m a big pro wrestling fan, so when I finally picked Haggar (I was always a fan of Cody) I marked out big time the first time I piledrived an Andore brother. Don’t even get me started on the Death Adder powerbombs… wow.

There’s a degree of risk involved. The grappling moves are flashier and stronger, but they often require you to literally walk into your enemies to grab them, and leave you wide open to other attacks. I’m a big pro wrestling fan, so when I finally picked Haggar (I was always a fan of Cody) I marked out big time the first time I piledrived an Andore brother. Don’t even get me started on the Death Adder powerbombs… wow.

Pizza time is party time

Here’s where things get really silly. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: The Arcade Game brought four players to the table at once; that in and of itself is a big deal that changed the scope of these kinds of games. Additionally, it also served as the beginning of another phase of brawlers: licensing! The relative simplicity of the genre allowed developers to cash in on popular properties, from the Ninja Turtles to Marvel comics to Hollywood blockbusters and more. It was an easy way to get people to notice a game, and the draw of four-player co-op action was hard to pass over.

Here’s where things get really silly. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: The Arcade Game brought four players to the table at once; that in and of itself is a big deal that changed the scope of these kinds of games. Additionally, it also served as the beginning of another phase of brawlers: licensing! The relative simplicity of the genre allowed developers to cash in on popular properties, from the Ninja Turtles to Marvel comics to Hollywood blockbusters and more. It was an easy way to get people to notice a game, and the draw of four-player co-op action was hard to pass over.

It didn’t always work so well. TMNT is certainly a shining example and holds up fairly admirably, but when you go back to games like X-Men and The Simpsons, the nostalgia gives way to banality very, very quickly. Do licenses serve to enhance the experience or cover it up? For that matter, does adding more players do the same, when levels and mechanics aren’t tailored toward making those players matter?

It didn’t always work so well. TMNT is certainly a shining example and holds up fairly admirably, but when you go back to games like X-Men and The Simpsons, the nostalgia gives way to banality very, very quickly. Do licenses serve to enhance the experience or cover it up? For that matter, does adding more players do the same, when levels and mechanics aren’t tailored toward making those players matter?

That’s a tough question. It’s always easier to overlook problems when you have a living room full of friends, but the more forgettable games are just that: forgotten. The mass of mediocre superhero and cartoon brawlers on the SNES are evidence of that. As far as multiplayer is concerned, sure, things get chaotic and messy, but outside of the mechanics there are few experiences that can match huddling around a cabinet as a group, smashing buttons and laughing as Magneto yells at you in broken English.

That’s a tough question. It’s always easier to overlook problems when you have a living room full of friends, but the more forgettable games are just that: forgotten. The mass of mediocre superhero and cartoon brawlers on the SNES are evidence of that. As far as multiplayer is concerned, sure, things get chaotic and messy, but outside of the mechanics there are few experiences that can match huddling around a cabinet as a group, smashing buttons and laughing as Magneto yells at you in broken English.

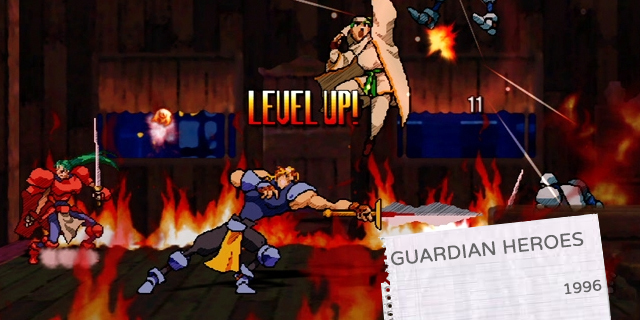

One game, many paths

Guardian Heroes brought the genre to the 32-bit era with a bevy of ambitious new features. The most famous was a branching storyline with multiple endings, influenced in part by karma built by your actions. It also sported a multiplayer versus mode, in which you could choose from almost any character in the game, including basic enemies and civilians. Instead of the usual vertical movement, Guardian Heroes separated the play field into planes, and players could jump from one to another as a way to quickly avoid damage. These features wouldn’t appear together often outside of other Treasure games, but Heroes did recently have a spiritual successor, Code of Princess for the 3DS.

Guardian Heroes brought the genre to the 32-bit era with a bevy of ambitious new features. The most famous was a branching storyline with multiple endings, influenced in part by karma built by your actions. It also sported a multiplayer versus mode, in which you could choose from almost any character in the game, including basic enemies and civilians. Instead of the usual vertical movement, Guardian Heroes separated the play field into planes, and players could jump from one to another as a way to quickly avoid damage. These features wouldn’t appear together often outside of other Treasure games, but Heroes did recently have a spiritual successor, Code of Princess for the 3DS.

It was at this point that brawlers really started to branch out. Do you think this was because of a desire for innovation and a creative resurgence, or was it simply that games were getting more complicated and that these games needed to become more convoluted to justify their existence? It’s hard to deny that the games’ new elements were largely for the better, but at least some were probably ill-advised.

It was at this point that brawlers really started to branch out. Do you think this was because of a desire for innovation and a creative resurgence, or was it simply that games were getting more complicated and that these games needed to become more convoluted to justify their existence? It’s hard to deny that the games’ new elements were largely for the better, but at least some were probably ill-advised.

I think complexity was definitely a thing in 32-bit games, even to the point of detriment. Just look at fighters, which in some ways aren’t terribly far removed from beat-’em ups. For a while there, if a game wasn’t complex, it wasn’t worth bothering with. In the case of Guardian Heroes, it was pretty niche to begin with, and a little less going on may have made it more approachable. That could be why some of its more distinctive features haven’t stuck around.

I think complexity was definitely a thing in 32-bit games, even to the point of detriment. Just look at fighters, which in some ways aren’t terribly far removed from beat-’em ups. For a while there, if a game wasn’t complex, it wasn’t worth bothering with. In the case of Guardian Heroes, it was pretty niche to begin with, and a little less going on may have made it more approachable. That could be why some of its more distinctive features haven’t stuck around.

Forging a dynasty

Dynasty Warriors approached all of the familiar bits and pieces of classic brawlers, and took them to the logical extreme within the PS2 generation’s 3D space. The sense of spectacle was exponentially increased, to the point of the player having near-godlike power. The scale of combat changed from one-versus-many to hundreds, if not thousands of enemies on screen, with boss encounters often being thrown into the chaos rather than separated. It seems like a huge difference on the surface, perhaps closer to the more technical hack-and-slash genre, but the tropes remain: lower end tech, simple but deliberate combat tools and a bunch of unthreatening, color-coded samey goons you have to get through before the boss at the end. Lately, we’ve even seen Tecmo Koei going after a bunch of silly anime licenses, coming full-circle with the brawlers of the nineties.

Dynasty Warriors approached all of the familiar bits and pieces of classic brawlers, and took them to the logical extreme within the PS2 generation’s 3D space. The sense of spectacle was exponentially increased, to the point of the player having near-godlike power. The scale of combat changed from one-versus-many to hundreds, if not thousands of enemies on screen, with boss encounters often being thrown into the chaos rather than separated. It seems like a huge difference on the surface, perhaps closer to the more technical hack-and-slash genre, but the tropes remain: lower end tech, simple but deliberate combat tools and a bunch of unthreatening, color-coded samey goons you have to get through before the boss at the end. Lately, we’ve even seen Tecmo Koei going after a bunch of silly anime licenses, coming full-circle with the brawlers of the nineties.

You could say that Dynasty Warriors’ weaknesses come from its strict adherence to the brawler formula. It’s the waves and waves of enemies that make it what it is, but to this day, it still has trouble handling all of those on-screen foes. It’s still about the slashing and running in a direction, even when it could be better served by having some strategic movements or interesting locales. I’m one of those who initially doubted the series’ ties to the genre, but the more you think about these underlying tenets, the clearer it is that it belongs.

You could say that Dynasty Warriors’ weaknesses come from its strict adherence to the brawler formula. It’s the waves and waves of enemies that make it what it is, but to this day, it still has trouble handling all of those on-screen foes. It’s still about the slashing and running in a direction, even when it could be better served by having some strategic movements or interesting locales. I’m one of those who initially doubted the series’ ties to the genre, but the more you think about these underlying tenets, the clearer it is that it belongs.

Absolutely. With Dynasty Warriors 8, Omega Force has addressed some of the major issues most folks have with the series, but it still struggles with all the on-screen chaos, especially if you’re trying to play online. It has toyed around with more pressing mission objectives, however, and even has surprise non-canon scenarios if you’re tenacious enough to find them. I’m definitely going to be eyeing the series once the new generation sets in to see what happens.

Absolutely. With Dynasty Warriors 8, Omega Force has addressed some of the major issues most folks have with the series, but it still struggles with all the on-screen chaos, especially if you’re trying to play online. It has toyed around with more pressing mission objectives, however, and even has surprise non-canon scenarios if you’re tenacious enough to find them. I’m definitely going to be eyeing the series once the new generation sets in to see what happens.

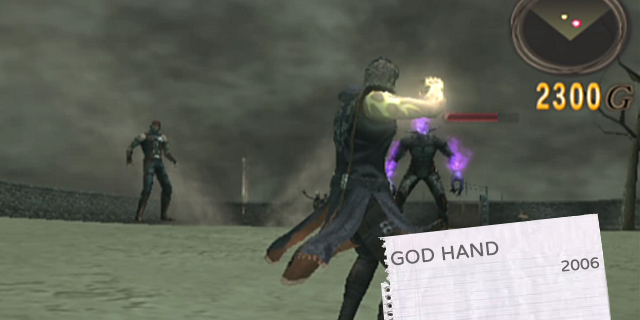

A new perspective

If Dynasty Warriors made use of 3D space to take the genre in a somewhat different aesthetic direction, God Hand used it to more directly convert brawlers for gamers of the 2000s. The perspective shifted to a behind-the-shoulder perspective with tank controls, but it felt exactly like a Final Fight or Double Dragon with newer, contemporary conventions and oddball Japanese humor. The enemies were mostly palette-swapped versions of distinct character types: normal guy, fat guy, female… while the bosses were large and inventive. It was appropriately difficult, with plenty of surprises for hardcore players. What God Hand added to the experience? Customizable combos. Players could map different kinds of moves to most of the available buttons. That, and a dodge move, gave players options beyond “punch or kick” or “light or strong attacks,” giving the beat-’em up previously unseen depth.

If Dynasty Warriors made use of 3D space to take the genre in a somewhat different aesthetic direction, God Hand used it to more directly convert brawlers for gamers of the 2000s. The perspective shifted to a behind-the-shoulder perspective with tank controls, but it felt exactly like a Final Fight or Double Dragon with newer, contemporary conventions and oddball Japanese humor. The enemies were mostly palette-swapped versions of distinct character types: normal guy, fat guy, female… while the bosses were large and inventive. It was appropriately difficult, with plenty of surprises for hardcore players. What God Hand added to the experience? Customizable combos. Players could map different kinds of moves to most of the available buttons. That, and a dodge move, gave players options beyond “punch or kick” or “light or strong attacks,” giving the beat-’em up previously unseen depth.

Clover, like Platinum after it, really leans into these simpler, macho sorts of character and plot archetypes. These have been largely thrown to the side in a genre that felt it needed to modernize, but these guys have been embracing them and putting them in other games entirely. What do you think about these sorts of tropes? Are they crucial to an authentic brawler, or something to simply tolerate? (Maybe both?)

Clover, like Platinum after it, really leans into these simpler, macho sorts of character and plot archetypes. These have been largely thrown to the side in a genre that felt it needed to modernize, but these guys have been embracing them and putting them in other games entirely. What do you think about these sorts of tropes? Are they crucial to an authentic brawler, or something to simply tolerate? (Maybe both?)

Neither! Platinum has a very high-octane, Japanese action cheeseball tone throughout most of their titles, and the hot-blooded machismo and other silliness is largely played for laughs. These tropes also lend themselves really well to the over-the-top style of their games, especially stuff like God Hand or MadWorld.

Neither! Platinum has a very high-octane, Japanese action cheeseball tone throughout most of their titles, and the hot-blooded machismo and other silliness is largely played for laughs. These tropes also lend themselves really well to the over-the-top style of their games, especially stuff like God Hand or MadWorld.

Better together

Coming from Newgrounds of all places, Behemoth’s Castle Crashers spearheaded a revitalization of beat-’em ups that made use of digital marketplaces to appeal to retro gamers with new games in addition to classic re-releases. Castle Crashers was 2D, hand-drawn and full of personality. Mechanically, it’s closest to Golden Axe, but it brought online play into the mix. While it had a smorgasbord of content, it didn’t bring anything particularly new to the table. However, it didn’t need to. The throwback style was a novelty of its own, and it brought the classic brawler back to the minds of gamers enough for more games to make appearances in the digital age: Double Dragon Neon, Phantom Breaker: Battle Grounds, Scott Pilgrim and Shank have all seen success since.

Coming from Newgrounds of all places, Behemoth’s Castle Crashers spearheaded a revitalization of beat-’em ups that made use of digital marketplaces to appeal to retro gamers with new games in addition to classic re-releases. Castle Crashers was 2D, hand-drawn and full of personality. Mechanically, it’s closest to Golden Axe, but it brought online play into the mix. While it had a smorgasbord of content, it didn’t bring anything particularly new to the table. However, it didn’t need to. The throwback style was a novelty of its own, and it brought the classic brawler back to the minds of gamers enough for more games to make appearances in the digital age: Double Dragon Neon, Phantom Breaker: Battle Grounds, Scott Pilgrim and Shank have all seen success since.

More and more, players aren’t meeting in one spot to play games. While I think that’s a shame, it’s a reality, and this shift to online at leasts lets players punch and kick together. Castle Crashers in particular has driven a lot of this look to XBLA as a place to play with friends. Is there something about the genre that makes it so effective at presenting this case to players?

More and more, players aren’t meeting in one spot to play games. While I think that’s a shame, it’s a reality, and this shift to online at leasts lets players punch and kick together. Castle Crashers in particular has driven a lot of this look to XBLA as a place to play with friends. Is there something about the genre that makes it so effective at presenting this case to players?

Brawlers are simple, easy to pick up and play, work super well for drop-in-drop-out play and are also almost entirely cooperative. You can generally relax, find any open game and have fun, without worrying about dominating the leaderboards.

Brawlers are simple, easy to pick up and play, work super well for drop-in-drop-out play and are also almost entirely cooperative. You can generally relax, find any open game and have fun, without worrying about dominating the leaderboards.

Futures that will and won’t be

Speaking of online play, Dungeon Fighter Online was a Korean MMO that took ideas from online games and smashed them into the mechanics of a brawler. Several different character classes were available, and along with the obvious basic skills, the usual MMO hotkey stuff was also present, incorporating skill trees and other familiar MMO trappings into the mix. A fatigue system also had players balancing their time spent on the game, as too much consecutive play had detrimental effects in-game. Unfortunately, as of this year, the servers are no longer online.

Speaking of online play, Dungeon Fighter Online was a Korean MMO that took ideas from online games and smashed them into the mechanics of a brawler. Several different character classes were available, and along with the obvious basic skills, the usual MMO hotkey stuff was also present, incorporating skill trees and other familiar MMO trappings into the mix. A fatigue system also had players balancing their time spent on the game, as too much consecutive play had detrimental effects in-game. Unfortunately, as of this year, the servers are no longer online.

Is this a one-off sort of thing that has met its end, or is this the sign of things to come? Where do you see the future of beat-’em-up genre taking us? I could see it relegated to the realm of nostalgia, and I could also see it finding a place to thrive.

Is this a one-off sort of thing that has met its end, or is this the sign of things to come? Where do you see the future of beat-’em-up genre taking us? I could see it relegated to the realm of nostalgia, and I could also see it finding a place to thrive.

We both know that MMO territory is about as stable as a set piece in an Uncharted game. That said, the game did last for several years before it shut down, but I just don’t see anything like it making a larger comeback. Beat-’em ups going forward are always going to be about the nostalgia factor. I doubt we’ll see any more God Hands, Bouncers or Viewtiful Joes in the near future, but as long as the digital marketplaces remain viable platforms for lower-budget-but-not-indie games, I’m sure we’ll continue to see them.

We both know that MMO territory is about as stable as a set piece in an Uncharted game. That said, the game did last for several years before it shut down, but I just don’t see anything like it making a larger comeback. Beat-’em ups going forward are always going to be about the nostalgia factor. I doubt we’ll see any more God Hands, Bouncers or Viewtiful Joes in the near future, but as long as the digital marketplaces remain viable platforms for lower-budget-but-not-indie games, I’m sure we’ll continue to see them.