In the early ’80s the home computer market flourished, with dozens of machines from myriad manufacturers, each with unique hardware gimmicks and software libraries. It was the Wild West of computing, seeing rapid expansion alongside a total lack of order. Big names like Atari, Commodore, Sinclair and IBM made their mark on the fledgling market in this era, competing to prove who had the machine with the most muscle.

One benchmark with which they could measure their computers’ strengths was gaming. As a young medium, video games were always pushing the limits of the meager hardware of the time. Thus, a well-programmed game was an effective way to wow consumers. In fact, games became just as popular in the very early days of home computing as actual work-related programs! This was especially true in Europe, where computers were far more popular than consoles amongst gamers until well into the 16-bit era.

Because of this, many of those same computer companies decided to break into the console market, as well. Nearly all of them proved to be dead on arrival. In fact, only one computer company was able to successfully make it in the market: Microsoft, with its Xbox. However, not many people know that the latter company’s oldest surviving rival came out with a game console of its own. We’re going to look at Apple’s Pippin.

The System

The Pippin was created during the period in which Apple allowed other manufacturers to license Mac OS for their own computers. In this case, Japanese conglomerate Bandai wanted to make a console based around the Macintosh Classic II, running a 16 MHz Motorola 68030 processor and the Mac System 7 OS.

These plans were soon scrapped, as the proposed specs paled in comparison to the Atari Jaguar, and even more so next to the upcoming Sega Saturn and Sony PlayStation. Instead, Apple proposed employing a newer PowerPC processor running at 66 MHz. While still considered low-end in the computer space at the time, it was notable for being one of the first-proposed Macs to run the PowerPC architecture.

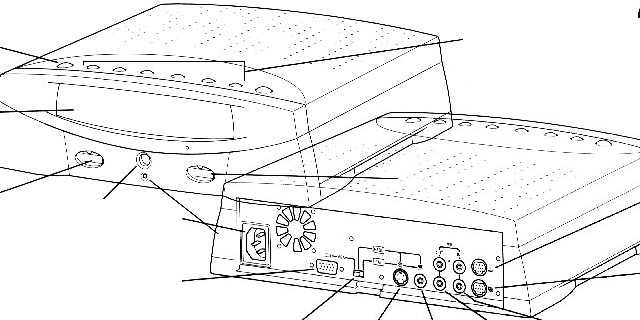

One of the goals of the Pippin project was to bring the capabilities of a Mac to a console, particularly, packing in a modem port (Though a modem itself was not built into the system). This approach was not unheard of in the ’90s – such devices were frequently referred to as Multimedia Devices or Internet Appliances.

The Pippin included its own web browser to compete in this space, and was touted as one of the system’s biggest features. While few games were able to make use of the capabilities, the web browser alone made the Pippin a unique curiosity for futuristic-minded gamers of the era.

Mac System 7 was the software base chosen for the Pippin OS. The operating system was cut down to fit on the console’s tiny ROM – let alone its even-smaller 16 KB of user-accessible Flash storage – but even then, it proved to be too expensive to build into every system. Thus, it was specified that all Pippin-compatible CDs contain the entirety of the OS.

This meant that applications could not be installed in Pippin OS; a CD had to be inserted to use the system’s basic functions, and only files small enough to fit in 16 KB of space could be shared between applications. That said, compared to peer consoles’ menus, Pippin OS was still superior. The System 7 base contained most of the functionality found on a Mac, but was unable to run Mac programs unless they were specifically ported. The opposite – however – was possible.

The Pippin’s “AppleJack” controller was a bizarre, banana-shaped contraption, bearing more than a passing resemblance to the eventual PlayStation 3’s prototype controller. It sported a circular directional pad, four face buttons, three navigation buttons on the bottom edge of the controller and – most notably – a trackball right in the center of the device. The trackball was primarily meant to compensate for a mouse when using the Pippin OS, but the positioning made it awkward and uncomfortable to use, even outside of games.

The Story

Planning within Apple for a game console actually began all the way back in 1979; employee Jef Raskin was heading three new hardware projects, one of which was to be the company’s entry into the console market. This made sense, as the Apple II was one of the more popular machines of its day, and more importantly was one of the first (arguably the first) home computers to offer color graphics.

However, Apple backed off after watching the downward spiral that was the games industry crash of 1983, and Raskin repurposed the existing hardware designs into what we know today as the Macintosh. The company’s approach to gaming for a long while after that was much more laissez-faire, not actively seeking out game developers, and instead focusing on the business and desktop publishing markets. While the Macintosh still received a hearty game library, its lack of color graphics made it clear that its capabilities there were pushed to the wayside.

As the ’80s came to a close, the IBM PC standard was beginning to take hold in the marketplace, forcing many proprietary computer makers out of the market. Apple was able to hold on to its tiny market share and avoid defeat throughout the ’90s. That said, times were still tough for the company, and it resorted to licensing out Mac OS to outside manufacturers to stay afloat. One such licensee was Bandai, who sought to break into the console market yet again after the previous failures of the Super Vision 8000 and Japanese distribution of the Arcadia 2001.

This time, the company wanted to make a platform standard for which games could be published, much like the 3DO attempted just before. The idea was to base it on an already well-known software platform (Mac OS), so that games made for computers could be easily ported. Plus, the Pippin OS would be designed so that Pippin games could run on comparable Macs.

In 1994, Bandai approached Apple with its plans for a low-end Mac inside a console shell, and Apple expressed interest. At the time, Apple had tried many experimental products to explore possible new revenue sources, such as cameras, printers and PDAs. A game console was relatively sane compared to some of its more outlandish products. Plus, as it could be mostly used as a traditional computer, it was not entirely uncharted territory. After some redesigns to make the system more competitive in the future, the Pippin was released in April 1995 in Japan, and September in America, for a whopping $600.

The important thing to understand about the Pippin’s failure was that, in an attempt to make a machine to compete in two markets, the result was an over-encumbered, overpriced machine that didn’t appeal to consumers looking for either. The intent to create a unified software platform also proved far too arrogant for such a machine, repeating the mistakes of the 3DO twofold while the 3DO was still on the market. The Pippin flopped hard and fast, ignored by a market that saw how clear it was that the Pippin was trying to solve a problem that didn’t exist.

A Swedish company called Katz Media soon licensed the Pippin hardware and software to be re-released as the Katz Media Player 2000. This did not last long, either, and was more positioned as a media set-top box, downplaying its gaming capabilities. Matsushita announced its plans to be a Pippin licensee at one point, but never followed through on those plans.

In the end, only an estimated 5,000 Pippins were ever sold to the public, bringing Bandai and Apple’s dreams of a single-platform future crashing to the ground. The system was not discontinued until 1997, but it was clear to consumers that it was dead as soon as it hit shelves.

The Possibilities

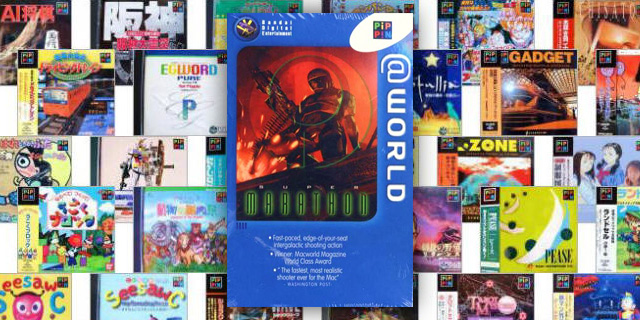

The Pippin’s intentions of being just as much a multimedia player and computer as it was a game console shone through in its software library, where the number of applications and edutainment titles outnumbered the traditional games. The multimedia craze was in full swing, and the Pippin was gaming’s proof of it. Most of the worthwhile titles for the console even make extensive use of its video capabilities (thanks to built-in support for the QuickTime plugin). Very few games on the Pippin are both exclusive and recommendable, and hardly any take advantage of its 3D muscle. Whatever potential the console had was never demonstrated in its games.

Some notable curiosities for the Pippin included Bungie’s Super Marathon, a compilation of the two Marathon games, made originally as Mac-exclusive first-person shooters. There was also a port of the computer adventure game Pegasus Prime, which was able to be nearly-perfect due to its video encoding. Due to Bandai’s backing, the Pippin also received its own Power Rangers and Gundam games. Neither are notably well-made, but their existence is interesting.

Many people today wonder why Apple doesn’t try to make a game console, considering its dominance in the mobile gaming scene. Those people are almost certainly unaware of the Pippin. Apple’s failed experiment scared the company away from the console market for good, and cemented its aversion to gaming until the App Store proved successful over a decade later. The Pippin tried to do too much and appeal to too many markets, and the result was a confused mess that couldn’t accomplish any of its goals. That spelled low sales and a minuscule game library, and not a single title was able to utilize the system’s potential.

Most famous failed game consoles have at least a couple of things that could make it worth checking out, be it interesting exclusives or a thriving homebrew community. The only people I can recommend the Pippin to are diehard Apple fans or hardware collectors. As the console is rare enough to still demand a premium, the only reason to buy a Pippin in this day and age would be sheer novelty of saying that you own the one and only Apple game console.