Emotional attachment to fictional characters is difficult to establish. Most people will suspend their disbelief to a point. They’ll buy into whatever world they’re seeing, as long as it makes some sense, the plot is coherent and, most importantly, they care about what happens to the characters. It’s an essential ingredient to any successful story.

Video games have it tough. How can you pace a game’s story properly when the user is in direct control of the experience? And how on Earth can you establish interest in the characters, when most video game dialogue ranks slightly below “tolerable” and far, far away from “good”?

Game characters usually get their development from cutscenes. Sure, you can get the satisfaction of growing stronger as you level up throughout the game. Really good games will show a character’s progression during the gameplay itself (thank you, Spec Ops: The Line!) and without breaking immersion (uh… good try, Spec Ops: The Line!). But the cutscene is most often where you’ll see a character talk, emote and take action.

For emotional attachment to happen, cutscenes need to be well-directed. Yes, just like a TV show or a movie. Does the blocking make sense? Why would a character move away from their love interest on that line? Are the animations correct? It’s a jarring experience to hear a good voice actor proclaim their innocence in a court filled with people, only to see the character begin jogging on the spot. It makes no sense. Graphics have evolved to the point where we are almost at photorealism, yet most game characters’ faces don’t quite look like ours. There’s a distinct uncanny valley present. We just don’t like it when something looks “almost” human. It either has to be 100% accurate or stylized to the point of it being cartoonish.

How do we get rid of these unpleasant cutscene quirks? How do we connect to users fully and get them invested totally in the characters? Their actions have to make sense, their faces have to move and look like ours, the voice acting has to be superb and the direction needs to be of high quality. The solution may be to use real actors.

Games have already started doing this. The Uncharted series has among the best voice acting, character animations and cutscene direction in the business. They’ve been using real actors since the first game came out in 2007. Most sports games have been using model athletes to get the fluidity of a point guard just right, or the skating ability of their cover athlete to look as realistic as possible. L.A. Noire experimented with this idea, to a shaky level of success. The team used highly-advanced facial animation technology to capture actors not just voicing their role, but playing it as well. Called “MotionScan,” this technology uses 32 cameras to record the actor’s blinking patters, eyebrow raises and mouth movements and converts them directly to the in-game animation. The result is a unique and imperfect experience, but certainly a step in the right direction for game immersion.

There are two games that really benefited from using real actors. The first? Mass Effect 2.

Despite what you think about the ending of the third game, the Mass Effect trilogy is fantastic. Going well beyond your standard space opera, Mass Effect has solid gameplay, absolutely fantastic environments, a deep history and, you guessed it, interesting characters that you really care about. One character really struck a chord with me. It wasn’t Mordin, that delightful Gilbert & Sullivan-singing Salarian Scientist Supreme. It wasn’t Garrus, the badass Turian soldier with a voice as calming as hot chocolate. No, it was the unforgettable Illusive Man.

The Illusive Man is the head of the Cerberus Corporation. He’s directly involved with putting you back together in the first hour of Mass Effect 2. You’re saved from death, resurrected with a few tweaks and are now expected to work for him. He claims his ultimate goal is to establish security for the human race. He may have other, more nefarious goals.

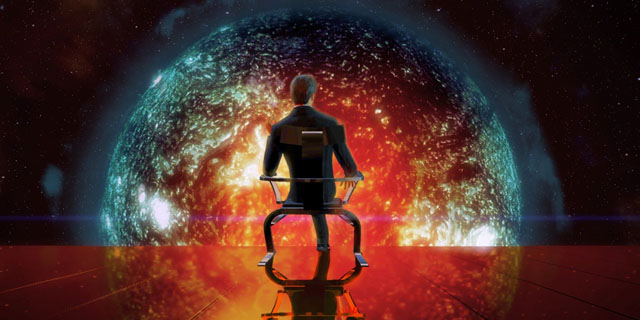

The character is a delight. He’s a normal-looking man (aside from the eyes) in his 50s. He has no outstanding physical features; he’s not particularly tall. He’s not charismatic, and certainly doesn’t have much of a sense of humor. And yet, he stands out as having a powerful, charming presence despite being in a game featuring more than a dozen unique alien races. You have a feeling that he’s always hiding something, but might actually be trusted. He sounds convincing when he claims he wants to protect humanity. He did rescue you, at great expense, after all. He’s usually calm and understanding, even when you disagree with him in conversations. Oh, and the only room you ever see him in (you never meet him face-to-face in Mass Effect 2) is a dark room, with a beautiful glass floor and a view that some would pay millions for. Glowing, fiery planets are really “in” this year, according to Citadel Real Estate Monthly.

This setting is highlighted nicely by the fact that he always has a cigarette in hand, and that he’s expertly portrayed by Martin Sheen.

Huh? Martin Sheen? You mean that Hollywood guy? That respectable, talented actor with over 50 years of experience in movies?

Yeah, that’s the guy. Not only does Martin Sheen have an absolutely perfect voice for this character, they modeled the physical features of the Illusive Man based on his appearance. Take one look at the Illusive Man and tell me he doesn’t look like a younger Martin Sheen. Why does this work?

Since the actor is experienced, the dialogue is good and the voice matches the physical form, we get a character we are interested in. Ask anybody who has played Mass Effect 2 (and 3) if they can remember what the Illusive Man sounds like. Without question, they will. There’s not a single person who has seen the Star Wars movies who can claim they can’t recall what Darth Vader’s voice sounds like? It’s impossible for the connection of Martin Sheen the actor and the Illusive Man character not to resonate with players. For those who haven’t, I highly encourage you to play through the entire Mass Effect series. For those who have, read this below line from the Illusive Man. Is Martin Sheen in your head yet?

“We’re at war. No one wants to admit it, but Humanity’s under attack. One very specific man might be all that stands between Humanity and the greatest threat of our brief existence.”

The second game is not part of an epic space opera. It didn’t sell tens of millions of copies. (Closer to a half-million.) But it’s a fantastic example of how using real actors can create characters that we care about through superior technology and acting. That game is Enslaved: Odyssey to the West.

Released in late 2010 for the Xbox 360, this action game went under the radar for most. The first thing I noticed about Enslaved was the graphics. The game looked good; smooth animations in battle, lush areas of a weird, post-apocalyptic world. Sure, it was linear and the combat and platforming were simplistic, but eventually I stopped caring about those factors because I grew to care about Monkey and Trip, the protagonists of the story.

Monkey is a strong, realistic, gritty warrior. He is less than pleased to find, upon escaping a prison ship and crash landing, that Trip has placed a slave collar on him. Monkey must obey her every command and if she dies, he dies. So begins the story.

I’m not going to say the game is a transcendent experience. Those with more knowledge of what makes “great” games will surely tell you that the game always reminds you that you’re playing a video game. It doesn’t have a revolutionary gameplay mechanic. You get the feeling you’ve done this before.

What you haven’t seen before, and what I grew to learn to appreciate, is the facial motion capture of Monkey (Andy Serkis, a.k.a. Gollum) and Trip ( Lindsey Shaw). This wasn’t just good voice acting. These sounded like real people who didn’t spout their dialogue like they were throwing up words. They were emoting properly. The facial reactions were uncannily realistic. I identified with both characters and wanted them to succeed. It helped that Trip isn’t a useless A.I. partner always in distress; you will need her help in fights, and she will help you without falling into a chasm. (Most of the time.)

They develop a relationship that is believable in an unbelievable setting. Epic fights with mechanized units and monstrous beasts occur, but the real connection comes from the quiet cutscenes with just Monkey and Trip. Take a look.

See how at 35 seconds, Trip actually looks sad? Not typical video-game sad, where the character would be frowning, or screaming, or crying. No, she looks scared. Visibly, but not over-the-top. She looks real. Now look at Monkey’s reaction to her first words. A subtle eye movement down, then back again. Not an overly-dramatic hug or exclamation of understanding. It looks real. You feel bad for Trip. You like Monkey for staying calm. No big, stupid speeches about how everything is going to be fine or some ridiculous attempt at comedy. This is a detail that only a human actor would know how to emote properly.

Granted, the head movements are a bit jerky and the character designs are Waterworld-esque, but the emotion is there. Watching this cutscene makes me want to play through the game again.

Alex Garland, the writer of Enslaved, deserves some credit. He is adapting a famous Chinese story (Journey to the West) to modern storytelling, in a venue where storytelling hasn’t been very good. Shaw and Serkis also deserve credit, as do the designers for picking seasoned actors. Upon being asked about Enslaved, Serkis had this to say:

“If you don’t feel in the moment of filming that the character is moving you or engaging you or transporting you somewhere, it won’t work. So you take that right into the recording of the dialogue. So it’s about trying to keep that dynamic — that relationship on stage — going, rather than having this scenario that normal games have where you just go to the booth and record your lines.”

As an actor, one of the best tools you have at your disposal are your fellow actors. Reactions and feeding off the energy of your acting partner can give you an immense boost of confidence, confirmation and emotion. This shows in Enslaved.

The ending of the game has moments of true beauty. It’s somewhat open-ended, but not as open-ended as, say, Halo 2 or Final Fantasy XIII-2. Some would call those endings “not-endings”. As Monkey and Trip, you end up in the fortress housing the main villain, Pyramid. Finally making sense of a series of flashbacks that Monkey saw throughout the game, we see Pyramid is a man. A real man, not a video game model. It’s an actor, with no facial mapping technology, or alien makeup or a mask.

It’s weird at first. You don’t often see real people in a game, but in this context it works. It works oh so well. Then he starts talking to you and you realize… that’s Andy Serkis, in the flesh. Even if you don’t recognize the famous Lord of the Rings actor, you do realize that you’re emotionally connected to this person in more ways than one. A mystery is solved (whose flashbacks were those?). A connection is made: hey, he’s real. A human being, talking to Monkey and Trip, characters I identify with. Is this meta?

Skip to 4:45.

“I have enslaved no one.” Pyramid (Andy Serkis) says after Monkey and Trip confront him, as he sits helpless before them.

Look at the sadness in his eyes. Listen to the sorrow in his voice. You won’t get that from a badly-animated, badly-acted character. You start feeling sorry for him. Him! The main bad guy!

“I am… an ark!”

See that smile? That quick, small smile? We can pick up on that.

“Their children go to schools. You have no schools.”

See the face shrink a tiny bit and Serkis’ voice lower on the “you have no schools” part? A sudden realization of sadness. It’s almost not even there. But because the game decided to use real actors to portray the characters, we see it’s there. We feel.

Using real actors may end up being too expensive. Big-budget games are already bloated as is, and many are predicting an end to these kinds of games. But I hope that the kind of technology that can bring us The Illusive Man, Monkey and Trip becomes cheaper and better. I want more “real actors” portraying my characters. These games certainly benefited from it.