Genre 101 looks at the past and present of a game genre to find lessons about what defines it. In this installment, Henry Skey joins Graham to discuss the foundational elements of the scrolling shooter.

Unidentified flying objects

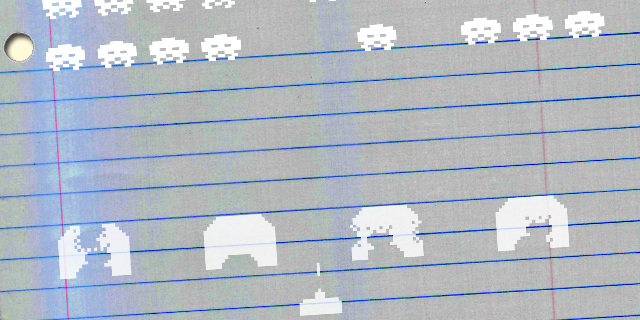

Henry Skey: If you made any kind of list of the most influential games of all time, Space Invaders unquestionably deserves a spot. It’s one of the classics; any retro arcade worth its salt will have at least one cabinet, and virtually everyone knows someone who has played it. Hideo Kojima and Shigeru Miyamoto were heavily influenced by the game, both claiming they weren’t even interested in video games until they saw it.

Henry Skey: If you made any kind of list of the most influential games of all time, Space Invaders unquestionably deserves a spot. It’s one of the classics; any retro arcade worth its salt will have at least one cabinet, and virtually everyone knows someone who has played it. Hideo Kojima and Shigeru Miyamoto were heavily influenced by the game, both claiming they weren’t even interested in video games until they saw it.

Graham Russell: In the early days, any innovative hit essentially created a genre, but even other nascent game types were driven by Space Invaders’ theme: alien invasion and space combat. Do you think that’s just its influence, or was there something about space and aliens that fit so well with the time or the technology?

Graham Russell: In the early days, any innovative hit essentially created a genre, but even other nascent game types were driven by Space Invaders’ theme: alien invasion and space combat. Do you think that’s just its influence, or was there something about space and aliens that fit so well with the time or the technology?

Space Invaders both cultivated and helped maintain this theme. A common trope among futurists in the ’50s and ’60s, technology was almost always related to space; flight outside our atmosphere, satellites going to the ends of the galaxy and cities on the moon. It helped that America got to the moon first and inspired millions to think about life beyond planet Earth. A combination of this wonder, and the fact that space is an easy background to program, made it a natural backdrop, and the fear of the unknown made aliens a compelling foe.

Space Invaders both cultivated and helped maintain this theme. A common trope among futurists in the ’50s and ’60s, technology was almost always related to space; flight outside our atmosphere, satellites going to the ends of the galaxy and cities on the moon. It helped that America got to the moon first and inspired millions to think about life beyond planet Earth. A combination of this wonder, and the fact that space is an easy background to program, made it a natural backdrop, and the fear of the unknown made aliens a compelling foe.

A long time ago in an arcade far, far away

Back in the late ’70s and early ’80s, you couldn’t find a hotter ticket than Star Wars. You could argue that rings true even today, but when the original movie was released in 1977, nobody had ever seen anything like it, and the world couldn’t possibly be prepared for the fallout. When the Star Wars arcade game found itself into arcades in 1983, another wave of entertainment euphoria hit. Fans got to experience, among other famous scenes from the movies, the Death Star trench run in full vector graphics glory. In true arcade fashion, you could never completely finish the game. Every time you “won,” the game would restart on a harder difficulty.

Back in the late ’70s and early ’80s, you couldn’t find a hotter ticket than Star Wars. You could argue that rings true even today, but when the original movie was released in 1977, nobody had ever seen anything like it, and the world couldn’t possibly be prepared for the fallout. When the Star Wars arcade game found itself into arcades in 1983, another wave of entertainment euphoria hit. Fans got to experience, among other famous scenes from the movies, the Death Star trench run in full vector graphics glory. In true arcade fashion, you could never completely finish the game. Every time you “won,” the game would restart on a harder difficulty.

The vector era is a weird one, as it allowed for depth and visual fidelity that we wouldn’t otherwise see for years, but various factors meant that the tech died out long before that day came. Yet its influence was in full effect once its mechanics could be replicated.

The vector era is a weird one, as it allowed for depth and visual fidelity that we wouldn’t otherwise see for years, but various factors meant that the tech died out long before that day came. Yet its influence was in full effect once its mechanics could be replicated.

You’re so right, and it won’t be the last time we see a technology that is simply too advanced for its own time. Vector graphics, though, never really stood a chance as more than a novelty. I’m sure many looked at Star Wars and thought that games were going to go this direction, only looking better and better. It would take decades for the technology to develop to a point when artists and programmers could actually fill in these 3D spaces. But you know that once it was available, they looked back at the success of this game as an indication of what players wanted. I imagine if you showed a modern Star Wars game to a kid in an ’80s arcade, his head would explode, so maybe it’s for the best that it took a while.

You’re so right, and it won’t be the last time we see a technology that is simply too advanced for its own time. Vector graphics, though, never really stood a chance as more than a novelty. I’m sure many looked at Star Wars and thought that games were going to go this direction, only looking better and better. It would take decades for the technology to develop to a point when artists and programmers could actually fill in these 3D spaces. But you know that once it was available, they looked back at the success of this game as an indication of what players wanted. I imagine if you showed a modern Star Wars game to a kid in an ’80s arcade, his head would explode, so maybe it’s for the best that it took a while.

Only the strongest survive

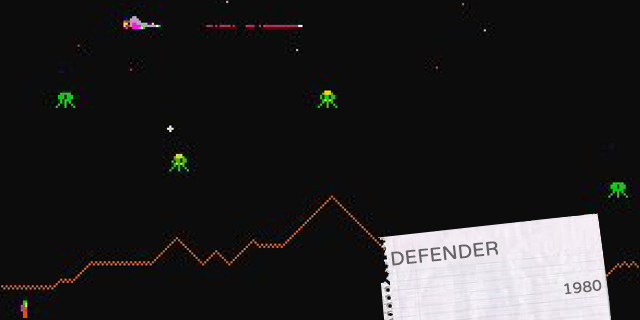

Eugene Jarvis saw Space Invaders and knew his destiny: creating something even more difficult. It had the sound and the look to draw people in, but the core gameplay lent itself to the hardcore and competitive play. Those who would call themselves masters would attempt to last as long as possible on a single quarter. That’s a Herculean task, considering most sessions last only a few short minutes. In terms of progression of the genre, it’s widely considered the first horizontal scrolling shooter.

Eugene Jarvis saw Space Invaders and knew his destiny: creating something even more difficult. It had the sound and the look to draw people in, but the core gameplay lent itself to the hardcore and competitive play. Those who would call themselves masters would attempt to last as long as possible on a single quarter. That’s a Herculean task, considering most sessions last only a few short minutes. In terms of progression of the genre, it’s widely considered the first horizontal scrolling shooter.

Shoot-’em-ups are often driven by the core of the core, a test of skill and reflexes only surmountable by talent and lots of practice. What is it about shoot-’em-ups that makes them so well-suited to this?

Shoot-’em-ups are often driven by the core of the core, a test of skill and reflexes only surmountable by talent and lots of practice. What is it about shoot-’em-ups that makes them so well-suited to this?

Pure game. With pinball, you’ll get the odd random bounce or faulty flipper, and your ball is doomed to the pit no matter how skilled you are. At a quick glance, it’s also difficult to tell how you’re doing; points stop having meaning when they approach random millions after a few minutes of play. With beat-’em-ups, you have a lot of room for error, as many had a life bar and teammates to cushion the difficulty. The shoot-’em-up, however, is king of the hardcore. Passersby can appreciate high-level skill at a glance. It’s easy to see everything; enemies and the player are almost always on the same screen. There’s something about completing something against impossible odds that draws a rush out of all us, and that’s shoot-’em-up at its core. Tight controls, clearly defined enemies and an encouragement of memorization meant that the hardcore gamers flocked to shoot-’em-ups, and still do today.

Pure game. With pinball, you’ll get the odd random bounce or faulty flipper, and your ball is doomed to the pit no matter how skilled you are. At a quick glance, it’s also difficult to tell how you’re doing; points stop having meaning when they approach random millions after a few minutes of play. With beat-’em-ups, you have a lot of room for error, as many had a life bar and teammates to cushion the difficulty. The shoot-’em-up, however, is king of the hardcore. Passersby can appreciate high-level skill at a glance. It’s easy to see everything; enemies and the player are almost always on the same screen. There’s something about completing something against impossible odds that draws a rush out of all us, and that’s shoot-’em-up at its core. Tight controls, clearly defined enemies and an encouragement of memorization meant that the hardcore gamers flocked to shoot-’em-ups, and still do today.

Cashing in on action-hero mania

Borrowing heavily from the Alien and Predator franchises, Contra was a landmark title. It was hard as nails, offering players no mercy: one-hit kills, tricky platforming sections and a seemingly endless supply of enemies. It also offered two-player simultaneous play. The attraction of grinding through one of the hardest games of all time with the help of a friend was too much to resist.

Borrowing heavily from the Alien and Predator franchises, Contra was a landmark title. It was hard as nails, offering players no mercy: one-hit kills, tricky platforming sections and a seemingly endless supply of enemies. It also offered two-player simultaneous play. The attraction of grinding through one of the hardest games of all time with the help of a friend was too much to resist.

It feels different than your standard scrolling shooter, but besides something resembling gravity holding down your movement, the formula’s similar: scroll sideways, shoot incredibly tough waves of enemies.

It feels different than your standard scrolling shooter, but besides something resembling gravity holding down your movement, the formula’s similar: scroll sideways, shoot incredibly tough waves of enemies.

Bingo. They nailed a common video game success formula; pick something that’s great and working and put your own spin on it. Aliens and Predator were two of the hottest movie franchises at the time, and it’s no conidence that the two main characters are essentially portraits of Arnold in his various action movies. If I had to pick one game that will age better than any on this list, I’d say Contra. The formula wasn’t revolutionary, but the fact that you can play a side-scrolling shooter with a friend puts it that far ahead of the pack. It was clear that players weren’t sick of going up against impossible odds and killing monsters, and developers noticed.

Bingo. They nailed a common video game success formula; pick something that’s great and working and put your own spin on it. Aliens and Predator were two of the hottest movie franchises at the time, and it’s no conidence that the two main characters are essentially portraits of Arnold in his various action movies. If I had to pick one game that will age better than any on this list, I’d say Contra. The formula wasn’t revolutionary, but the fact that you can play a side-scrolling shooter with a friend puts it that far ahead of the pack. It was clear that players weren’t sick of going up against impossible odds and killing monsters, and developers noticed.

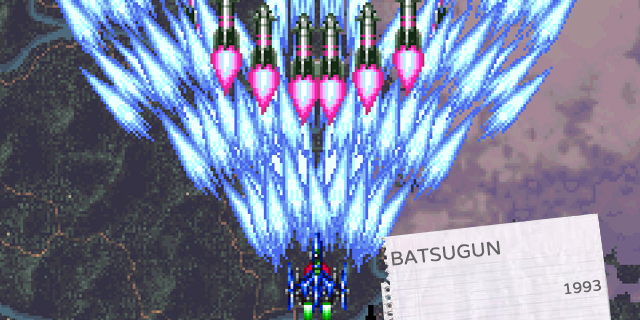

Dodge and shoot, but mostly dodge

Call it a manic shooter. Call it bullet hell. Call an asylum, because this game is the definition of insanity. If Space Invaders is the founding father, this is the energy drink-fueled teenager with nothing to lose. Batsugun went beyond the definition of what shoot-’em-ups had to offer, introducing complex enemy waves and bullet patterns. Instead of priming the player to focus all their energies on hitting the bad guys, Batsugun switched the focus to dodging. Memorization and a comfortable feel of the ship’s hit box, along with lightning-quick reflexes, were paramount if you are to survive more than a few seconds.

Call it a manic shooter. Call it bullet hell. Call an asylum, because this game is the definition of insanity. If Space Invaders is the founding father, this is the energy drink-fueled teenager with nothing to lose. Batsugun went beyond the definition of what shoot-’em-ups had to offer, introducing complex enemy waves and bullet patterns. Instead of priming the player to focus all their energies on hitting the bad guys, Batsugun switched the focus to dodging. Memorization and a comfortable feel of the ship’s hit box, along with lightning-quick reflexes, were paramount if you are to survive more than a few seconds.

With the advent of the danmaku (bullet hell) game, did the genre push itself too far? Did it leave its mainstream appeal behind in this fervent pursuit of the ultimate challenge?

With the advent of the danmaku (bullet hell) game, did the genre push itself too far? Did it leave its mainstream appeal behind in this fervent pursuit of the ultimate challenge?

They say the line between madness and genius is razor thin. On the one hand, you offer an incredible challenge unseen in any game. Casual players will take one look and say it’s impossible. They simply won’t believe that a person with normal instincts and reflexes could maneuver their ship through that amount of enemy fire. That’s appealing to the most hardcore of players, as every person telling them they can’t do it gives them a greater resolve to defeat it. That said, it might have done more harm than good to the genre. I mean, if you cover every pixel of the screen with enemy fire from the first level on, where is there to go next? How do you entice players with future games when you’ve already shown your hand?

They say the line between madness and genius is razor thin. On the one hand, you offer an incredible challenge unseen in any game. Casual players will take one look and say it’s impossible. They simply won’t believe that a person with normal instincts and reflexes could maneuver their ship through that amount of enemy fire. That’s appealing to the most hardcore of players, as every person telling them they can’t do it gives them a greater resolve to defeat it. That said, it might have done more harm than good to the genre. I mean, if you cover every pixel of the screen with enemy fire from the first level on, where is there to go next? How do you entice players with future games when you’ve already shown your hand?

Moving away from quarter-focused design

Throwing out conventional wisdom, Radiant Silvergun (developed by the aptly named Treasure) provides the player absolutely no power-ups. Instead, there are seven different weapons available based on button combinations, allowing for incredibly deep design and a challenge unseen in the genre at the time. Specific sections are more easily passed with the right weapon selection, adding a sense of personal progression and trial-and-error that went beyond dodging a million enemy bullets. Destroying specific combinations of enemies allowed quicker upgrades of weapons, and a robust story (a rarity for shoot’em ups) means that Radiant Silvergun’s legacy will remain for a very long time.

Throwing out conventional wisdom, Radiant Silvergun (developed by the aptly named Treasure) provides the player absolutely no power-ups. Instead, there are seven different weapons available based on button combinations, allowing for incredibly deep design and a challenge unseen in the genre at the time. Specific sections are more easily passed with the right weapon selection, adding a sense of personal progression and trial-and-error that went beyond dodging a million enemy bullets. Destroying specific combinations of enemies allowed quicker upgrades of weapons, and a robust story (a rarity for shoot’em ups) means that Radiant Silvergun’s legacy will remain for a very long time.

Shoot-’em-ups have never really escaped the arcade-centric influences of their forefathers, but Radiant Silvergun was one of the first to start to acknowledge a shift away from quarter-munchers past and toward something that players could sink their teeth into for months and years at a time.

Shoot-’em-ups have never really escaped the arcade-centric influences of their forefathers, but Radiant Silvergun was one of the first to start to acknowledge a shift away from quarter-munchers past and toward something that players could sink their teeth into for months and years at a time.

I’m still shocked that some gaming personalities will come out and say story doesn’t matter at all in games. I would think that statement false 20 years ago, and today it’s downright stupid. Radiant Silvergun borrowed heavily from Neon Genesis Evangelion, and fans adored the cutscenes, story and characters, no matter how cliche they were. They’d never seen story in a shoot-’em-up before, and it clearly was a major factor in Radiant Silvergun’s success.

I’m still shocked that some gaming personalities will come out and say story doesn’t matter at all in games. I would think that statement false 20 years ago, and today it’s downright stupid. Radiant Silvergun borrowed heavily from Neon Genesis Evangelion, and fans adored the cutscenes, story and characters, no matter how cliche they were. They’d never seen story in a shoot-’em-up before, and it clearly was a major factor in Radiant Silvergun’s success.

Two polarities are better than one

If a game is lucky, it’ll find the right audience and the recognition it deserves. Ikaruga, despite a lack of any kind of advertising budget, has been ported from its original Dreamcast home, where very few experienced it, to the GameCube, Xbox Live Arcade and now Steam. A clear evolution of Radiant Silvergun, Ikaruga borrowed the combo system and no-powerups feature and added the genius element of polarity switching. With the touch of a button, you can change your ship’s color from white to black or black to white. Whatever color you are, you absorb that kind of enemy fire and do double damage to enemies of the opposing color, while being susceptible to their attacks. The controls are tight, the aesthetics are beautiful, the action is frantic and absorbing attacks instead of being at their mercy is a phenomenal paradigm shift.

If a game is lucky, it’ll find the right audience and the recognition it deserves. Ikaruga, despite a lack of any kind of advertising budget, has been ported from its original Dreamcast home, where very few experienced it, to the GameCube, Xbox Live Arcade and now Steam. A clear evolution of Radiant Silvergun, Ikaruga borrowed the combo system and no-powerups feature and added the genius element of polarity switching. With the touch of a button, you can change your ship’s color from white to black or black to white. Whatever color you are, you absorb that kind of enemy fire and do double damage to enemies of the opposing color, while being susceptible to their attacks. The controls are tight, the aesthetics are beautiful, the action is frantic and absorbing attacks instead of being at their mercy is a phenomenal paradigm shift.

This is the way genres usually evolve: with one key innovation. It’s weird, though, that shoot-’em-ups generally didn’t try the “one new thing” model for a long time, focusing on overwhelming players with lots of stuff they’ve already seen in different combinations. Why do you think this took as long as it did?

This is the way genres usually evolve: with one key innovation. It’s weird, though, that shoot-’em-ups generally didn’t try the “one new thing” model for a long time, focusing on overwhelming players with lots of stuff they’ve already seen in different combinations. Why do you think this took as long as it did?

Why did the adventure game largely fade away until Telltale’s The Walking Dead? What happened to the beat-’em-up? The industry, just like the rest of the world, follows trends. Shoot-’em-ups were so popular for so long that it was inevitable they take a downward trend eventually. Is it because, by nature, they’re not as fun anymore? I don’t buy that, but I think the market was oversaturated and people moved to emerging genres for their fix. It doesn’t mean that people don’t enjoy these types of games anymore; they’re just not the only ticket in town. Ikaruga had the benefit of lowered expectations; it wasn’t a fifth Call of Duty game, nor did it have decades of history behind it. It came out of nowhere, from a developer that looked at what made previous games successful and created a beautiful product based on a single, simple idea.

Why did the adventure game largely fade away until Telltale’s The Walking Dead? What happened to the beat-’em-up? The industry, just like the rest of the world, follows trends. Shoot-’em-ups were so popular for so long that it was inevitable they take a downward trend eventually. Is it because, by nature, they’re not as fun anymore? I don’t buy that, but I think the market was oversaturated and people moved to emerging genres for their fix. It doesn’t mean that people don’t enjoy these types of games anymore; they’re just not the only ticket in town. Ikaruga had the benefit of lowered expectations; it wasn’t a fifth Call of Duty game, nor did it have decades of history behind it. It came out of nowhere, from a developer that looked at what made previous games successful and created a beautiful product based on a single, simple idea.

What’s old is new again

It’s held the record for most-downloaded game on the Xbox Live Arcade and spawned countless clones, and it brings us full-circle. The look and feel are borrowed from classic games of old, such as Asteroids, Centipede and Space Invaders. The controls are pleasingly easy (one joystick moves your ship, the other fires projectiles), and the levels are maddeningly difficult. Its sequel offered the same core design, but many more modes, ensuring that this is a franchise that will have a place in past, present and future dashboards.

It’s held the record for most-downloaded game on the Xbox Live Arcade and spawned countless clones, and it brings us full-circle. The look and feel are borrowed from classic games of old, such as Asteroids, Centipede and Space Invaders. The controls are pleasingly easy (one joystick moves your ship, the other fires projectiles), and the levels are maddeningly difficult. Its sequel offered the same core design, but many more modes, ensuring that this is a franchise that will have a place in past, present and future dashboards.

It seems like every installment of this series has ended, or almost ended, with a game that’s stripped everything away and focused on the bare essentials of the genre. In this case, it’s a back-to-basics focus on beating high scores and competing with friends. Could this have been done before Geometry Wars, or did we need a networked console world for this kind of game to be created?

It seems like every installment of this series has ended, or almost ended, with a game that’s stripped everything away and focused on the bare essentials of the genre. In this case, it’s a back-to-basics focus on beating high scores and competing with friends. Could this have been done before Geometry Wars, or did we need a networked console world for this kind of game to be created?

I don’t think it could. Geometry Wars came at the exact right moment, right around the time when the Wii and smartphones were expanding the gaming population like we’d never seen before. Older gamers were starting to play games with their children, but also with groups of friends and on their own. Geometry Wars tapped into their nostalgia — the simple, basic premise of a ship shooting aliens — and gave it an HD remake. It wasn’t just a slap of paint either; it had enough depth to be addictive and the community to entice you to try just one more round. Anybody can understand friends and competition, no matter what the format. Leaderboards and YouTube videos helped Geometry Wars be a socially-fueled hit in much the same way as Space Invaders.

I don’t think it could. Geometry Wars came at the exact right moment, right around the time when the Wii and smartphones were expanding the gaming population like we’d never seen before. Older gamers were starting to play games with their children, but also with groups of friends and on their own. Geometry Wars tapped into their nostalgia — the simple, basic premise of a ship shooting aliens — and gave it an HD remake. It wasn’t just a slap of paint either; it had enough depth to be addictive and the community to entice you to try just one more round. Anybody can understand friends and competition, no matter what the format. Leaderboards and YouTube videos helped Geometry Wars be a socially-fueled hit in much the same way as Space Invaders.

GIFs by Christian Stewart.