Video games are a powerful bonding tool, yes. Games are a great excuse for a social gathering, great for keeping in touch with your friends, great for reminiscing about the good ol’ days. Remember when you were a kid and you played that game for days?

Well, what about when you actually are a kid. What do they mean? Hours and hours of entertainment, yes. Blowing up things and killing people in a relatively consequence free, fictional universe? Yes, but take note. All the stuff we like about video games — being a more attractive, clever superhuman who happens to be either way more social, way more fit, sexy, ruthless and adept at creating and destroying worlds — is significantly cooler when you’re a kid.

Your mind is a video game blank slate. You don’t have to think about things like “I wonder how the developer did this” or “what should I make for dinner tonight” or “I wonder how long a bill has to be overdue before anything will happen?” All you have is your imagination, innocence and wonder. Combine that with video games, and you have a recipe for an incredible experience. You know how you keep going on and on about how one game gives you such a sense of nostalgia you can almost taste it? Well, this is where nostalgia was born. This is the nostalgia motherland. Nostalgia makes pilgrimages to your childhood, when you first discovered games.

One of the reasons playing video games as a kid can be awesome is the control it gives them. I’m not talking about specific controls, I mean actually having the power and ability to directly control a digital avatar and influence the events set in front of them. That’s a powerful feeling. I’m not sure if you remember being a kid, but I’ll bring you back up to speed; you don’t have a lot of control in your life. You don’t shop for your own clothes, you don’t pick your school, you don’t eat whatever you want. You have to go sleep when mom and dad say so. You have to do homework when they say so. Being a kid can suck.

Thankfully, being a kid was absolutely the greatest thing ever. Like when you built that huge castle out of Legos. Or a massive city made out of playing cards. You could entertain yourself effortlessly with a little spare time (which you had) and a little creativity (which I hope you had). Jumping on the bed, running through fields and getting dirty were certainly highlights for me, but games had a different impact. And parents have a lot to do with that.

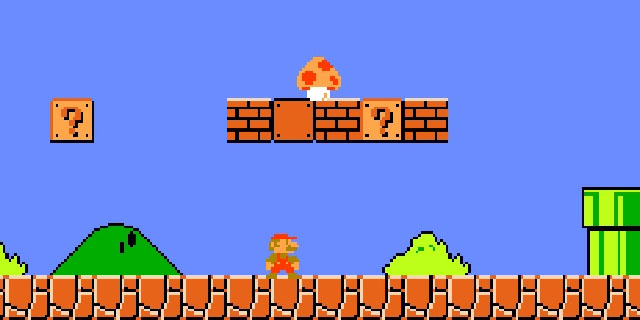

I’m sure it’ll happen to me. In 10 or 15 years, I’ll be watching my 6-year-old playing with something that will look ridiculous. I’m sure I’ll mutter something about how back in my day, money used to flutter from the ceilings of heaven or some nostalgia-bullshit-driven drivel. But if I’m a good parent, I’ll ask what they’re doing and take interest. Hopefully they’ll be excited about this prospect and teach me the inner workings of DNA Play-Doh replicating or Mr. Hugosaurus, or whatever it is they’ll be playing with in 2027. It doesn’t really matter what the object of explanation is; kids enjoy explaining things to their parents. With video games, we have an opportunity for kids to interact with cool worlds and feel empowered by explaining the inner workings of the game to parents. No dad, that’s a mushroom. You have to catch that. Because it makes you big, it transforms you and you’re stronger. Sound familiar?

I’m not going to give parents advice on how to raise their kids. I don’t know how video games affect children on any kind of level. Without a lot of research and expertise, I don’t think many do. What I do know is that I loved explaining the games I was playing to my parents. And I really, really enjoyed spending time with my dad when he would take the time to play some games with me.

SimCity 2000 was a perfect game to play alongside my dad, who was not what you would call a “gamer”. Most of our parents didn’t grow up playing games, certainly video games weren’t a part of their childhood and weren’t a large part of the consumer world. Dad did, however, like games. And being an engineer by trade, SimCity 2000 held great appeal to him. I wanted to have the biggest population, but he was more interested in how many people took the train to work each day. How was our plumbing? Our taxes were too high. “Even in video games, taxes are too high!,” he would proclaim, until realizing we’d have to cut back on the railroad budget if he lowered taxes.

My dad doesn’t like cars. He loves boats and trains. Bikes and planes are definitely more than acceptable. But after years of commuting to work each and every day, and not liking cars to begin with, my dad could not drive again for the rest of his life and be the happiest person on the planet. If Canada somehow plunged 15 feet into the Pacific, he’d be doing handstands with a glass of wine in his hand, wearing a party hat.

So when it came to designing our ultimate city of Fish Hooks in SimCity 2000, the polite civil war was on between my side of the city (the one with roads) and his side of the city. His side was a hippie’s smoke-induced dream: almost no roads, just train tracks everywhere, and a subway system that would have made Escher shake his head in disbelief. We had a blast checking the stats each day. “Why isn’t anybody taking the bus? I would take the subway to work each day, why are people driving?” For a city named after fishing apparatus and dad’s love for boats, you’d think we’d have picked a map with more water. I don’t think there was an ounce of H20 on the entire map. Poor guy.

Even though we argued a bit about our city’s ultimate plan, we giggled at making funny signs (that soon dominated the visual landscape, thank you designers for having a function to hide them!), planning transportation routes and where to build our next bio-dome. I wouldn’t have enjoyed the game half as much without dad by my side.

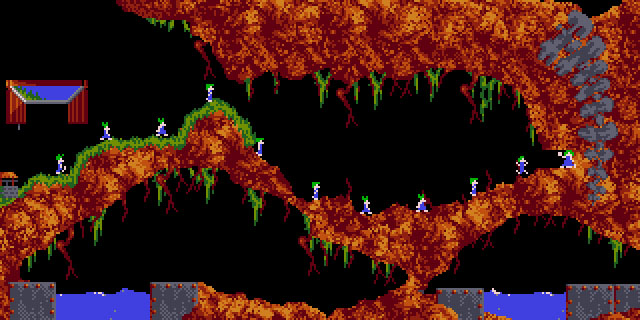

We wanted to try a puzzle game next. A game that would test our will and patience. Something we could play together. Lemmings was that game.

Lemmings was a PC game that had you assign various tasks to multiple green-haired whatevers in an effort to guide as many as possible to the exit of a level. They would drop in and immediately start walking. It was up to you to make them block, bash, build and blow up their way to freedom. The problem was that I was only 8 years old at the time, and I couldn’t figure out many of the levels. Twenty years later, this hasn’t changed, but when I was living with my parents, dad was my cheat guide.

We’d play the levels together, each watching the path that the Lemmings would take and together (mostly him), we’d figure out what to do. I had full control of the mouse, because I had to do something and it certainly wasn’t figuring out that we had to send a lone Lemming on the upper level of the concrete maze and have him meet up with the group at the very end. Or that we had to build 5 staircases, not 6, because we needed the extra stairs at the end of the level. We beat nearly every level there was, sometimes only by the skin of our teeth (Lemmings‘ words, not mine). Dad saw things that I didn’t. I was eager to carry out his commands with a quick push of a button, resulting in Lemmings jumping out the exit and us jumping out of our chairs with excitement.

My parents’ only rule regarding games was that I had to get my homework and studying done first, and no games during final exam period. And that was that. I often wondered what they thought of me playing games at a young age. They can’t have ignored it; I asked for video games every year for Christmas until I was 23. Most parents realize now that video games aren’t just a passing fad, but a mad passion for many, myself included.

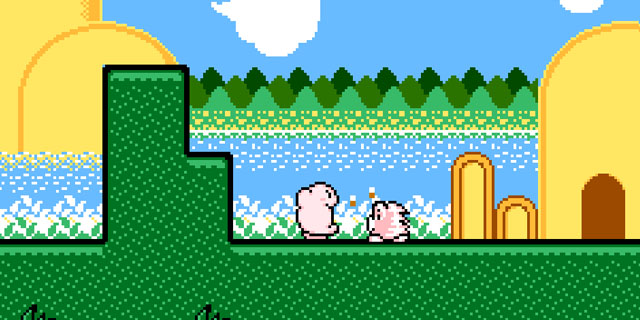

Recently at a family dinner, the subject of video games came up. They both agreed that violent games and movies aren’t their cup of tea. My sister and I tried to explain the appeal of The Hunger Games and failed. What they did like were non-violent, fun, puzzle games. Dad piped up. “Like that paper airplane game! (Glider 3).” Mom mentioned she liked watching me play Kirby on the NES. She also mentioned that she didn’t mind me playing games, but that was because I did lots of other things; sports, theatre, reading. To her, balance was as important as the hobbies themselves. There was a reason I had very few limits on my playing time.

It was interesting getting their perspective years later. At the time, I knew that dad might play SimCity 2000 or Lemmings with me, and that mom didn’t like me playing video games before school because I was making us late. Regardless, they had an influence on my favorite hobby. I was encouraged by dad. We didn’t have individual victories, only shared successes. Mom’s watchful eye ensured I never became too enamored with just games, and it never stopped her from phoning me from our local video rental store, asking me which game I would like her to rent for me. I’d somehow forgotten that until now. I hope she knows how grateful I am for her doing that.

I hope you had positive experiences with your parents and video games. I only use video games in this example because, well, I’m writing for a video game site and that was my own personal experience. But whatever your hobby was as a kid, I hope it’s still your hobby. I hope you love it as much now as you did back then. I hope you can talk to your parents about it, and share quiet details that you may have forgotten and remind yourself of how much they supported you. I know that’s not the case with everybody, and for those who it isn’t, I hope you find somebody who does love you and support you the way my parents did when I was 8 years old; eager to create and influence my own fantastic worlds, but even more eager to explain them and invite others to enjoy them alongside me.

Love you both.