Hatsune Miku is not real.

That’s the first thing you really have to get out of the way when introducing people to the world of Miku, but it’s possibly the least relevant. Behind the computer-generated voice and appearance are actual songs by real creators, making Hatsune Miku and her “vocaloid” colleagues much like a Japanese spin on Gorillaz.

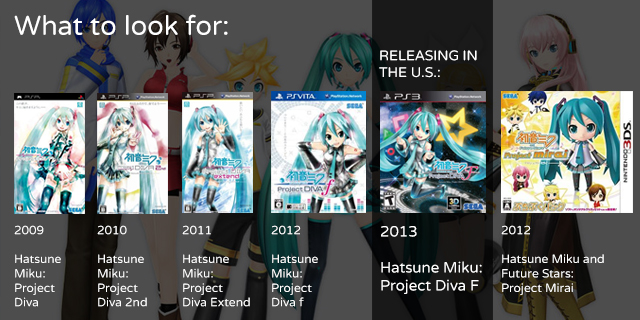

A virtual music act, especially one with such domestic popularity in Japan, makes for an ideal subject for a game. Japan has seen years of installments in Sega’s Project Diva series, and next week the U.S. receives its first localized installment. Now seems like a good time to learn about the faces, gameplay and history of Miku’s rhythm game outings.

Import File:

Hatsune Miku

Released in U.S.: Hatsune Miku: Project Diva F (PS3, 2013)

Not released in U.S.: Project Diva (PSP, 2009), Project Diva 2 (PSP, 2010), Project Diva Extend (PSP, 2011), Project Diva f (Vita, 2012), Hatsune Miku and Future Stars: Project Mirai (3DS, 2012)

Developer: Sega

Publisher: Sega

Language barrier: Minimal. It’s a rhythm game, so all you have to do is figure out how to get through the menus, and they’re straightforward.

Vocaloids, as they’re called are created using software developed by Yamaha, and the most successful creator has been Crypton Future Media. Hatsune Miku wasn’t the first Crypton creation; that honor goes to Meiko, who has stuck around the Project Diva crew despite being first-generation tech. All of these voices are designed for software users to make songs of their own creation, but these looks and personalities developed from software box art and took lives of their own.

Besides Miku and Meiko, the usual Project Diva roster includes blue-haired male Kaito, the bespectacled Megurine Luka and young twins Kagamine Rin and Len. It’s no fluke that the roster is mostly female, and not just because of the Japanese pop scene; as it is, male Vocaloid voices (and English ones, for that matter) are generally less convincing and natural-sounding. There are occasional appearances from other characters (and sometimes real singers), but most of the time, it’s just these six. (And Miku dominates much of the lineup.)

There’s a lot more to learn if you wish, but you need precisely none of it to enjoy playing a rhythm game. Of course, you do need to enjoy the music. To see if it’s something you’d like, check out this playlist from the most recent game’s Japanese release. Vocaloid songs are generally known for their inherently accurate vocal timing, and make use of tricks that are hard (or impossible) for real humans. Styles vary, but you’ll regularly find incredibly-fast runs of syllables and simultaneous vocal harmonies.

As with practically all super-Japanese series in the past decade, Project Diva started on the PSP. Generally, it hasn’t changed that much, but there have been tweaks that I’ll get to later. The basic setup: button symbols appear on screen, in somewhat creative formations that approximate the rhythm. Matching symbols slowly approach the target, and when the two line up is when you need to press the button. Of course, if you rely on that, you’ll be sunk. Knowing the rhythm of the songs is key to success, so if you haven’t heard one, expect your first play to be a very educational disaster.

On easier difficulties, you have fewer buttons to juggle, and on higher difficulties, there are more occasions when you’ll need to hit both the button and the direction on the D-pad that corresponds to that button’s position. (That’s also important to note: on single notes, the two are interchangeable, so mastery of harder songs comes from knowing when to use each.)

This remained the formula through the game’s sequel (and Extend, a sort of standalone expansion), but with the Vita version, “star” notes were added that required touch-screen flicks. It’s possible that this idea came from the iOS Miku Flick games, though those aren’t considered to be very good or accessible to Westerners. Since the PS3 release (that we’re getting) is based on the Vita one, the star notes remain, and are triggered by flicking the analog stick. Thankfully, the series hasn’t gotten too complicated, so the West-bound F remains a great starting point.

A warning: Project Diva isn’t the easiest rhythm game. The scoring can be quite brutal; if you miss a few notes at the wrong times, you can lose special section bonuses and dip below a passing grade. You certainly can’t look at any of the intricate CG music video behind the notes, or you’re sunk.

It’s weird, then, that the game puts lots of its progression into unlocking items and costumes for the characters that you can give them customize these videos. It varies some from game to game, but you also get to put them in a room and decorate it. It’s weird. I don’t know.

If you’re looking for something a bit different, you’ll find it in Hatsune Miku’s 3DS outing, Project Mirai. The game uses super-chibi versions of the Vocaloid stars (based on the Nendoroid figure line) and generally cuter, more upbeat songs. The mechanics are very different, but you’re still hitting buttons. A line goes around a circle, and you hit button prompts when the line reaches them. Mirai is both the hardest to import (3DS isn’t region-free) and the most likely to be localized next (since it’s more viable than the PSP or Vita), but it’s not exactly representative of the franchise.

With sequels to both Diva f and Mirai on the way, Hatsune Miku games aren’t going anywhere, but this may be the West’s one shot at playing them. If rhythm games aren’t objectionable to you and you like the idea of weird games with English localizations, maybe take a look?