The games I cover in this column are for social gaming, generally for groups from three to six, and even sometimes up to twelve. Occasionally some of these accommodate two players, and a few are for one-on-one play exclusively, but what do you do while you’re waiting for your friends to show up? Some variant of solitaire is always an option, I guess, but designer Shadi Torbey has another option: Onirim (published by Z-Man Games).

Onirim is, at its core, a deck of seventy-six cards. Eight of these cards are Doors, which are your objective and come in pairs of four different colors (brown, red, blue, and green). In order to find these doors, you will have to play Labyrinth cards. In the base game, all Labyrinth cards are Chambers. Chambers come in those same four colors and also bear either a sun, a moon, or a key symbol.

On each turn, you can play one card in front of you, with the only restriction being that the symbol of the card played cannot match that of the one played before it. Should you manage to play three Chamber cards of the same color in a row, you may go through the deck, find one of the matching doors, and then reshuffle. Alternately, you may discard a card that you have no use for. Should you discard a key, you gain the power of Prophecy, which allows you to look at the top five cards of the deck, remove one from the game (this is mandatory), and then rearrange the remaining four in any order.

After playing or discarding a card, you must then draw one. At this point, one of three events can happen. One: you draw a Labyrinth card. Nothing special happens here. Two: you draw a Door card. If you have a key of the matching color in your hand at this point, you may discard it to score the Door immediately! If you do not, set the Door aside (in the “Limbo” pile) and draw again. Unfortunately, the other option is that you draw a Dream card.

In the base set, the only Dreams in the deck are Nightmares. Drawing one of these forces you to make a tough choice. The easiest way to dismiss a Nightmare is to discard a Key from your hand. A slightly more costly method is to reveal the top five cards of the deck and discard any of those that are Chambers (setting additional Dreams and Doors in Limbo). If you’re feeling particularly brave you can discard your hand to appease the Nightmare. But even that would be preferable to the final option: returning a Door that you’ve earned to Limbo. However you get past the Nightmare, it is discarded and will haunt you no more, although its damage has undoubtedly already been done.

This draw step, and its consequences, repeats until you either have five Chamber cards in hand or you’ve exhausted the deck. Once you have five cards in hand, take all of the cards set aside in Limbo and shuffle them back into the deck before continuing with your play/discard. If you’ve exhausted the deck, however, you have become lost in the labyrinth and the game has defeated you. You only win when you manage to find all eight Doors, which is much easier said than done, believe me.

What makes Onirim difficult, other than the Nightmares, is the fact that the distribution of colors and symbols among the Chamber cards is somewhat uneven. Each color has only three keys and four moons, with the rest of their number bearing suns. Further complicating matters is that each color has a different amount of cards. The six brown sun cards are all you’ll get, and there are one, two and three more suns in the green, blue and red Chambers (respectively). You have to know this if you want to succeed. Knowing the relative value of each color’s suns is vital. Red suns are cheap and plentiful, almost every brown card is precious, while blue and green lie somewhere in between.

While managing your suns is a key skill, that is nothing compared to the power of the actual keys. Discarding a key to trigger a Prophecy is, without question, your most important action. Knowing if any Nightmares are lurking on top of the deck – and even more crucially, being able to remove one from the deck before it strikes – will make or break your chances of success. If there are more problems on top of the deck than you can contain, try to orchestrate finding a Door before you draw them, as that will trigger a reshuffle.

Having a key in hand when a corresponding Door shows up is nice, but doesn’t seem to happen that often in my experience, although this too is something you might be able to orchestrate with skillful use of Prophecy (and some fortunate draws, admittedly). Don’t be afraid to play a key when no moon is available, but see if you have any other option first. That being said, bear in mind that whenever a Door is found from a sun-moon-sun sequence, your next card must be one of your precious moons or keys in order to continue.

Onirim includes a two-player variant, in which you and your partner play your own separate rows of cards. Other than that, the main difference between this and the solo version is that each player has a hand of three cards, plus two shared cards face-up on the table. When discarding, a player may exchange a card in their hand for one of the shared cards if desired. These shared cards are considered to be part of that player’s hand, with all five being discarded should a Nightmare require that solution. Players alternate turns until they have both found one of each Door or they lose to exhausting the deck. The level of communication allowed between the players is up for them to agree upon at the beginning of the game.

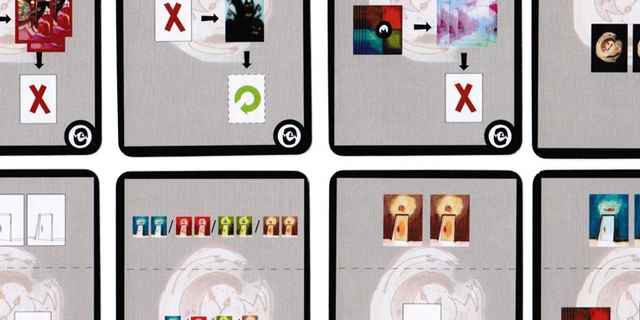

Should the seventy-six base cards of Onirim not prove challenging enough, the box also includes three expansions. In “The Book of Steps Lost and Found,” you set out eight Goal cards that dictate the order in which you must discover the eight Doors… as if just finding all eight in any order wasn’t difficult enough already. You also have access to three Spells, each powered by removing cards from your discard pile (each spell has two costs depending on the level of difficulty you desire). These Spells can let you put four of the top five cards of the deck on the bottom (at the cost of five or six cards), swap two Goal cards (seven/nine cards), or banish a Nightmare without punishment (a painful ten/twelve cards). You won’t be able to use these too often, but they will undoubtedly come in handy.

“The Towers” adds twelve Tower cards to the deck (three of each color), which are treated as Labyrinth cards when drawing them. Forming an Alignment of Towers (one of each color) is now an additional requirement to victory. Towers have sun and moon symbol on their sides and are played in their own row as long as you don’t place matching symbols next to each other. When discarded, Towers let you rearrange a number of cards on the top of the deck equal to the number printed on the bottom of the discarded Tower.

Nightmares force the destruction of a played Tower in addition to however else you choose to deal with them; you can destroy any Tower, as long as doing do doesn’t result in matching symbols being adjacent on the ones left behind. Alternately, you can choose to not destroy a Tower, but in that case the Nightmare is placed into Limbo and eventually reshuffled instead of being discarded after you pay whatever other cost you decide. Fortunately, an Alignment of four colored Towers is immune to destruction… unless you really hate yourself and choose to ignore that rule.

Finally, “Dark Premonitions and Happy Dreams” adds four non-Nightmare Dreams to the deck. As might be inferred from the expansion’s title, it also adds eight Dark Premonitions. Four (or more, if you’re a masochist) of these Dark Premonitions are dealt face-up, and tell you both their trigger condition and what happens when that trigger comes to pass, which always involves a specific combination and/or number of Doors. None of these effects are pleasant, and a few of them even cause new Dark Premonitions to be revealed, which can trigger immediately if conditions are right (or wrong). Encountering a Happy Dream gives you three options: 1) remove a Dark Premonition, 2) a super-Prophecy that looks at the top seven cards of the deck and can remove as many as you wish before putting the rest back in the order of your choice, or 3) take any one card from the deck, shuffle the deck, and then put the chosen card on top.

These expansions can be combined as you wish, and are all compatible with two-player play as well. That’s a lot of value in one tiny ten-dollar box of cards. Of course, the difficulty of even the base version of Onirim can be too much for some. For those timid individuals, there’s always good old solitaire. For the rest of us, we can dare to dream of solving the labyrinth while waiting for friends.