Wizards of the Coast (a subsidiary of Hasbro since 1999) is best known for their collectible card game phenomenon Magic: the Gathering, now approaching its 20th anniversary, but they are also the current publishers of the nearly 40-year-old Dungeons & Dragons RPG (since WotC purchased TSR in 1997). In the past, they have branched off into more traditional board games, previously under their Avalon Hill brand name (such as RoboRally, Vegas Showdown and others), although that brand has been essentially retired for some time now.

They still release a few board games, however. Lately these have been adaptations of their powerful D&D brand, providing a similar experience as the RPG but without any actual role-playing. Their latest offering, Lords of Waterdeep, also mines an established D&D setting for its theme, but with its wooden cubes, worker placement and victory points, it’s unmistakably a traditional Eurogame.

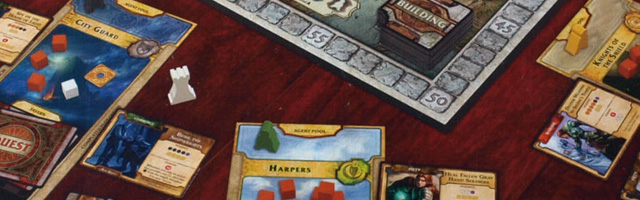

Lords of Waterdeep is an eight-round affair for two to five players as they vie for control of the titular city. Each player starts with at least four gold (determined by starting turn order), a player-dependent number of agents (workers, meeples… whatever you want to call them, but the game is a bit more fun if you run with the D&D theme naming), with an additional agent made available to them starting in round five; they are also each dealt two quests, one of the eleven Lords of Waterdeep cards (which offer additional VP at game end for completing specific types of quests), and two Intrigue cards.

The goal of the game is to gain the most influence (VP), and the most common way to achieve this is by completing Quests. Each quest has a requirement of fighters, clerics, rogues, and/or wizards (represented by the various wooden cubes), plus often a gold investment; after placing an agent, a player may complete one of their quests by paying the necessary resources, at which point they receive the quest’s rewards. Most quests are completed and then placed face-down on the player’s tavern (play mat), but some are “plot quests” that provide lingering benefits once completed and are kept face up on the other side of your tavern so you can remember what they do.

The other main source of VP comes from constructing buildings to develop the city. Three advanced building tiles are placed next to Builder’s Hall at the start of the game, and every round a VP chip is placed on each one. When a player assigns an agent to the Builder’s and pays the building’s gold cost, they earn all of the VP that has accumulated on that tile. The constructed building is placed on one of the vacant spaces on the board (buildings can exceed the number of spaces, although this is rare) and a control marker of the constructing player is placed in the notched corner. Any player may assign an agent to that building to claim its benefit, but if an opponent does so then the owner receives the reward indicated (paid from the stock, not from the opponent).

Besides advanced buildings, the board has several basic buildings that provide minor benefits (the Builder’s Hall is one such location). As with almost all worker placement games, only one agent can be assigned to any given building, with two exceptions. Additional quests can be obtained from a face-up array of four by assigning an agent to one of the three spaces at Cliffwatch Inn; each space provides a different benefit in addition to the quest card, one of which is the ability to discard the four current quests before choosing.

Intrigue cards can only be played by assigning an agent to one of the three spaces at Waterdeep Harbor. After all players have assigned their available agents, any agents at the Harbor (in the order assigned) can then be reassigned to a non-Harbor location, if any remain. After eight rounds of agent-placing and quest-completing, players score one additional VP for every adventurer (and every two gold, rounded down) left in their tavern, then score any bonus VP granted by their Lord card. The highest score wins, with gold serving as tiebreaker if necessary.

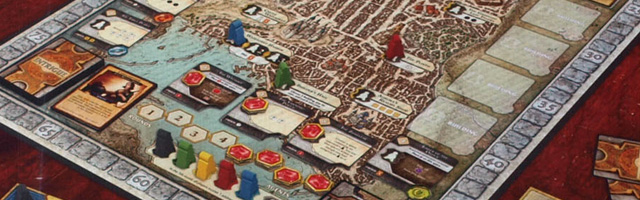

Lords of Waterdeep obviously owes a lot to several games that came before it, but most worker-placement games tend to feel the same superficially so it is both difficult and pointless to pin down which specific ones. Mechanically, what really makes it stand out from its brethren are the Quests. In most other worker-placement games, the resources you accumulate with your actions have specific ways in which they can be spent (often by using another of your precious actions to do so). In Lords of Waterdeep, the spending is a free action that you can do every time you place an agent, if you can afford to.

This is made up for somewhat by the insanely limited number of agents made available: a two player game provides four each initially, but four and five players only receive two! That’s only twenty total actions (plus reassignments and other chicanery) over the course of the game, and with much more competition than with just one opponent. There’s only so much you can accomplish with a paltry two actions a round, so you have to make them count. That’s where the “building owner” mechanic comes into play, as the advanced buildings both provide much stronger actions than the basic ones as well as potentially providing side benefits to a non-active player, creating the illusion of additional actions. Many Intrigue cards also allow non-active players to receive side benefits, although some actively attack the other players. Thanks to these effects, the two-player game is a much different experience from having three or more.

There is one other area that makes Lords of Waterdeep unique, and it comes from an under-utilized aspect of board games: the box insert itself. If you thought Small World‘s was awesome — and I did — you will be utterly amazed by Waterdeep‘s. Four bowl-like reservoirs hold the adventurer cubes; since they are round-bottomed, scooping out cubes is effortless. This same engineering concept extends to the card/tile holders, which have additional space under either end that allows you to push down on one end to lift up the entire stack, under which the unique pawns (start player, special agents) are stored. Coins, VP, agents and other tokens have assigned spaces that hold them tightly, and the board itself fits snugly on top of everything to hold it all in place, even when stored vertically. There is no need for bags and rubber bands here; whoever designed this insert deserves some sort of medal. Despite the spectacular insert and high-quality components, Lords of Waterdeep still retails for only $50.

A session of Lords of Waterdeep will rarely take more than an hour thanks to the eight-round structure and limited number of actions per player per round. The recommended age is twelve and up; there is quite a bit of reading required here (mostly the Intrigue cards), and you really have to plan ahead while weighing various options. It really isn’t anything ground-breaking, but the quick play, strategic decisions, and elegant design combine for an enjoyable experience that doesn’t drag on, and set-up is a breeze thanks to the effort that went into packaging.