Genre 101 looks at the past and present of a game genre to find lessons about what defines it. To wrap up this semester, Graham’s joined by Jeff deSolla to talk about what would become the modern Western RPG.

Opening new worlds

Jeff deSolla: Western RPGs have long been seen as more open experiences than their Japanese counterparts, often focusing on a world rather than the characters and story. While the Ultima series has always done this to a certain extent, Ultima IV is the game that really started to capitalize on the idea. The plot is really open, as your only goal is to become the Avatar, a figure who lives up to the ideals of virtue and chivalry. Much like the open-world RPGs of today, Ultima IV focused on a lot of morality choices and open-ended dungeon exploration instead of guiding the player through scripted plot events.

Jeff deSolla: Western RPGs have long been seen as more open experiences than their Japanese counterparts, often focusing on a world rather than the characters and story. While the Ultima series has always done this to a certain extent, Ultima IV is the game that really started to capitalize on the idea. The plot is really open, as your only goal is to become the Avatar, a figure who lives up to the ideals of virtue and chivalry. Much like the open-world RPGs of today, Ultima IV focused on a lot of morality choices and open-ended dungeon exploration instead of guiding the player through scripted plot events.

Graham Russell: Is it this openness that distinguishes Western RPGs as a genre from other role-playing games? Can a true Western RPG have a linear structure?

Graham Russell: Is it this openness that distinguishes Western RPGs as a genre from other role-playing games? Can a true Western RPG have a linear structure?

Openness is one of the most common aspects of a Western RPG, but not the only one. There are many that still hold to a directed narrative, even if the world is immense. The Elder Scrolls particularly comes to mind here.

Openness is one of the most common aspects of a Western RPG, but not the only one. There are many that still hold to a directed narrative, even if the world is immense. The Elder Scrolls particularly comes to mind here.

A gateway to the masses

Baldur’s Gate has a lot of firsts. As part of the initial wave of Windows-only games, it was also on the forefront of the move to a CD-ROM from piles of floppy disks. While the Dungeons & Dragons universes have long been a source of role-playing games on PC, none before had managed to break out of the niche. Free of the size restrictions imposed by both small hard disks and the slow access times of floppies, Baldur’s Gate was able to build a visually stunning world that drew in players both familiar with and new to the D&D setting, with a combination of high-resolution pre-rendered graphics and extensively voiced roles.

Baldur’s Gate has a lot of firsts. As part of the initial wave of Windows-only games, it was also on the forefront of the move to a CD-ROM from piles of floppy disks. While the Dungeons & Dragons universes have long been a source of role-playing games on PC, none before had managed to break out of the niche. Free of the size restrictions imposed by both small hard disks and the slow access times of floppies, Baldur’s Gate was able to build a visually stunning world that drew in players both familiar with and new to the D&D setting, with a combination of high-resolution pre-rendered graphics and extensively voiced roles.

How much of Baldur’s Gate’s success was due to its association with Dungeons & Dragons? It seemed to tap into that community, through its structure and general appeal as well as through an official tie to its lore.

How much of Baldur’s Gate’s success was due to its association with Dungeons & Dragons? It seemed to tap into that community, through its structure and general appeal as well as through an official tie to its lore.

The Dungeons & Dragons name was well-known, as was the Forgotten Realms setting. This gave BioWare a ready-made universe, complete with mechanics, locations and character classes to build atop. This cut down on a lot of unknowns for a new developer, and allowed the team to focus on building the engine that made the game work.

The Dungeons & Dragons name was well-known, as was the Forgotten Realms setting. This gave BioWare a ready-made universe, complete with mechanics, locations and character classes to build atop. This cut down on a lot of unknowns for a new developer, and allowed the team to focus on building the engine that made the game work.

It’s all just shades of gray

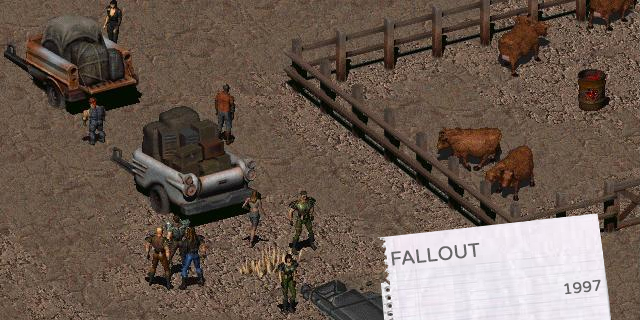

Like many games, Fallout offers a morality system, though the options aren’t always black and white: many times you find yourself choosing between two terrible outcomes. The game spends a lot of time driving home the point that the wasteland is not a friendly place. One of the biggest differences from previous games: your story progress has no bearing on content. You can skip ahead in the story either by knowing map locations or by random exploration. Finding a relevant plot area or item will often allow you to skip large chunks of the story, or cause you to see it in a different order.

Like many games, Fallout offers a morality system, though the options aren’t always black and white: many times you find yourself choosing between two terrible outcomes. The game spends a lot of time driving home the point that the wasteland is not a friendly place. One of the biggest differences from previous games: your story progress has no bearing on content. You can skip ahead in the story either by knowing map locations or by random exploration. Finding a relevant plot area or item will often allow you to skip large chunks of the story, or cause you to see it in a different order.

Fallout shows how the genre isn’t necessarily bound to a fantasy setting, as much as it can usually be found there. There are other titles that branch out as well, but they’re not common. Why do you think it’s so tough for developers to explore new themes, especially given how well games like Fallout have done?

Fallout shows how the genre isn’t necessarily bound to a fantasy setting, as much as it can usually be found there. There are other titles that branch out as well, but they’re not common. Why do you think it’s so tough for developers to explore new themes, especially given how well games like Fallout have done?

I think the biggest danger is that going into other settings often leads to other genres. If you’re making a science fiction game, the presence of projectile weapons like guns will often end up with the game moving away from an RPG and toward a first- or third-person shooter, like in Mass Effect 2. While a fantasy setting could just as easily lead to an action game, the trappings of science fiction often don’t work as well in an RPG due to the slower pacing.

I think the biggest danger is that going into other settings often leads to other genres. If you’re making a science fiction game, the presence of projectile weapons like guns will often end up with the game moving away from an RPG and toward a first- or third-person shooter, like in Mass Effect 2. While a fantasy setting could just as easily lead to an action game, the trappings of science fiction often don’t work as well in an RPG due to the slower pacing.

Making worlds feel real and full

While the Elder Scrolls series has existed since mid ’90s on PC, it really stepped it up with Morrowind. Aside from the many technical advances in Morrowind, it jumped to the Xbox, becoming the first big open-world RPG on a console. Morrowind took advantage of advancing tech to put in voiced characters and create the island of Morrowind in 3D, improving upon its sprite-based, texture-recycling past. Two more installments would be released to critical acclaim, Oblivion and Skyrim, but neither made the immense jump Morrowind did both for the series and the genre.

While the Elder Scrolls series has existed since mid ’90s on PC, it really stepped it up with Morrowind. Aside from the many technical advances in Morrowind, it jumped to the Xbox, becoming the first big open-world RPG on a console. Morrowind took advantage of advancing tech to put in voiced characters and create the island of Morrowind in 3D, improving upon its sprite-based, texture-recycling past. Two more installments would be released to critical acclaim, Oblivion and Skyrim, but neither made the immense jump Morrowind did both for the series and the genre.

Even though the definitive versions of Elder Scrolls games are inevitably the PC ones, there’s a definite tie between the series and console success. What did Morrowind (and, later, Oblivion and Skyrim) do from a gameplay perspective to make it more accessible to that audience and in that context?

Even though the definitive versions of Elder Scrolls games are inevitably the PC ones, there’s a definite tie between the series and console success. What did Morrowind (and, later, Oblivion and Skyrim) do from a gameplay perspective to make it more accessible to that audience and in that context?

Because these RPGs are first-person titles, the rise of the console FPS trained players to use dual analog for camera and movement. Success on console is often linked to a low learning curve, due to the way console players consume games compared to PC players; giving them a relatively familiar set of controls worked wonders.

Because these RPGs are first-person titles, the rise of the console FPS trained players to use dual analog for camera and movement. Success on console is often linked to a low learning curve, due to the way console players consume games compared to PC players; giving them a relatively familiar set of controls worked wonders.

Putting players in control

Following the huge success of Baldur’s Gate and its sequels and spinoffs, BioWare set out to create not just another D&D-focused title, but an all-encompassing experience with user-created campaigns and the introduction of a Dungeon Master to control them. With an incredibly diverse set of tools, Neverwinter Nights gave players the ability to turn the game into anything. Its multiplayer system was used to turn it into everything from a hack-and-slash game to a D&D-based MMO with a persistent world. Neverwinter Nights offered a fully realized single-player experience, but its real contribution was showing just what modding could add to a Western RPG if players are given the right tools.

Following the huge success of Baldur’s Gate and its sequels and spinoffs, BioWare set out to create not just another D&D-focused title, but an all-encompassing experience with user-created campaigns and the introduction of a Dungeon Master to control them. With an incredibly diverse set of tools, Neverwinter Nights gave players the ability to turn the game into anything. Its multiplayer system was used to turn it into everything from a hack-and-slash game to a D&D-based MMO with a persistent world. Neverwinter Nights offered a fully realized single-player experience, but its real contribution was showing just what modding could add to a Western RPG if players are given the right tools.

While Baldur’s Gate certainly appealed to D&D players, Neverwinter Nights became (for some, anyway) an interesting substitute for the original dice-rolling experience. Of course, as good as mods are, this focus on customization does come with some trade-offs in polished, professional storytelling and world-building.

While Baldur’s Gate certainly appealed to D&D players, Neverwinter Nights became (for some, anyway) an interesting substitute for the original dice-rolling experience. Of course, as good as mods are, this focus on customization does come with some trade-offs in polished, professional storytelling and world-building.

Much like the real-world D&D, actually. Often, a home-grown campaign won’t offer the level of detail found in a purchased professional adventure, yet it can also have more meaning to the players as something only they have played. Neverwinter Nights allowed people to get this experience in a video game, though many never really saw it at its greatest unless they played with friends. It’s also the first time that remote D&D play was feasible, long before virtual tabletop sites became popular.

Much like the real-world D&D, actually. Often, a home-grown campaign won’t offer the level of detail found in a purchased professional adventure, yet it can also have more meaning to the players as something only they have played. Neverwinter Nights allowed people to get this experience in a video game, though many never really saw it at its greatest unless they played with friends. It’s also the first time that remote D&D play was feasible, long before virtual tabletop sites became popular.

Building around big choices

Using experience with science fiction settings gained in its work with Star Wars, BioWare crafted its own back story for the Mass Effect trilogy. Beyond story and setting, what sets Mass Effect apart is how much control the player is given over the character’s path. The story follows the same general route, but the decisions made by the player can determine which team members live and die and which methods are used to achieve their goals. Completing side missions and exploring the world can also unlock new options during story segments. Morality and player choice have been covered in earlier games, but never with the quality found in Mass Effect.

Using experience with science fiction settings gained in its work with Star Wars, BioWare crafted its own back story for the Mass Effect trilogy. Beyond story and setting, what sets Mass Effect apart is how much control the player is given over the character’s path. The story follows the same general route, but the decisions made by the player can determine which team members live and die and which methods are used to achieve their goals. Completing side missions and exploring the world can also unlock new options during story segments. Morality and player choice have been covered in earlier games, but never with the quality found in Mass Effect.

Mass Effect certainly has skill trees and conversation choices, but it’s still very much an action-shooter at times. Yet it’s still more of an RPG than action-focused games with similar progression elements. Why is that? What does it do that others don’t?

Mass Effect certainly has skill trees and conversation choices, but it’s still very much an action-shooter at times. Yet it’s still more of an RPG than action-focused games with similar progression elements. Why is that? What does it do that others don’t?

While the series has moved back and forth between action-shooter and RPG, it’s often a matter of public perception. Purely based on the presence of progression and stat allocation, we could consider Call of Duty’s online mode to be an RPG, but most wouldn’t think of it that way. Genres are becoming blurrier all the time, but it comes down to the fact that the games were marketed as RPGs as much as anything else.

While the series has moved back and forth between action-shooter and RPG, it’s often a matter of public perception. Purely based on the presence of progression and stat allocation, we could consider Call of Duty’s online mode to be an RPG, but most wouldn’t think of it that way. Genres are becoming blurrier all the time, but it comes down to the fact that the games were marketed as RPGs as much as anything else.

Ambition and rewarding mastery

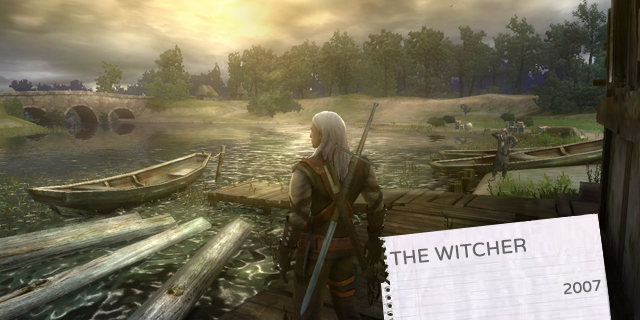

In the console-dominant mid-2000s, nobody really expected a PC-exclusive title to take off — especially not an RPG from an independent team. The Witcher was a bit of a sleeper hit; it wasn’t originally featured on Steam, and it had a small retail presence, but Internet buzz really caused it to take off. Avoiding a BioWare-style morality system and bearing a hybrid RPG-action combat system that made it feel more engaging than simply standing next to an enemy and swinging a sword, The Witcher gave players a steeper learning curve and a bigger feeling of accomplishment. The level of detail put into the game is impressive, with an immense quantity of side content: much of this possible because PCs aren’t restricted by install size, giving the developers the freedom to create more detailed cities and environments.

In the console-dominant mid-2000s, nobody really expected a PC-exclusive title to take off — especially not an RPG from an independent team. The Witcher was a bit of a sleeper hit; it wasn’t originally featured on Steam, and it had a small retail presence, but Internet buzz really caused it to take off. Avoiding a BioWare-style morality system and bearing a hybrid RPG-action combat system that made it feel more engaging than simply standing next to an enemy and swinging a sword, The Witcher gave players a steeper learning curve and a bigger feeling of accomplishment. The level of detail put into the game is impressive, with an immense quantity of side content: much of this possible because PCs aren’t restricted by install size, giving the developers the freedom to create more detailed cities and environments.

The Witcher is basically the Crysis of RPGs, pushing technical boundaries on its way to photorealism and visual flair. It seems to fit, too. To what extent does having such detailed environments enhance the Western RPG experience?

The Witcher is basically the Crysis of RPGs, pushing technical boundaries on its way to photorealism and visual flair. It seems to fit, too. To what extent does having such detailed environments enhance the Western RPG experience?

For PC enthusiasts, pushing limits is important. It’s why people pay $600 for a video card, when a $200 card will still provide a good experience. I think CD Projekt RED understands the mind of the PC enthusiast very well: they want to build the best looking game they can, because the people with these machines want something to challenge them. Like a high-end racing car, the things being done at the very limits of technical boundaries will inevitably filter down into the games that follow.

For PC enthusiasts, pushing limits is important. It’s why people pay $600 for a video card, when a $200 card will still provide a good experience. I think CD Projekt RED understands the mind of the PC enthusiast very well: they want to build the best looking game they can, because the people with these machines want something to challenge them. Like a high-end racing car, the things being done at the very limits of technical boundaries will inevitably filter down into the games that follow.