In From Pixels to Polygons, we examine classic game franchises that have survived the long transition from the 8- or 16-bit era to the current console generation.

Sega’s Sonic the Hedgehog series, once considered as the rival franchise to Nintendo’s Super Mario Bros., has gone on to become a cultural phenomenon. Despite some troubled developments in recent years, the Sonic series has remained incredibly popular and, to this day, one of Sega’s key franchises. With the recent announcement of Sonic Lost World, we thought it would be the perfect time to look back at Sega’s mascot and explore just how far he’s come since the days of the Genesis.

Sega’s new mascot races onto the scene

With the launch of Sega’s new console, the Genesis (or Mega Drive outside of the United States), the company wanted to try something a little different. While its previous attempts to give its company a mascot with Alex Kidd never panned out, Sega was still desperate to find a character that could rival Nintendo’s Italian plumber. And thus, Sonic the Hedgehog was born, and with his creation came a franchise that continues to live on to this day.

With the launch of Sega’s new console, the Genesis (or Mega Drive outside of the United States), the company wanted to try something a little different. While its previous attempts to give its company a mascot with Alex Kidd never panned out, Sega was still desperate to find a character that could rival Nintendo’s Italian plumber. And thus, Sonic the Hedgehog was born, and with his creation came a franchise that continues to live on to this day.

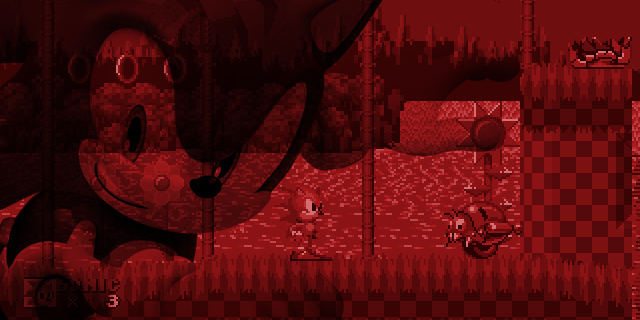

The original Sonic the Hedgehog focused less on precise platforming and more on speed, giving Sonic a trait that separated him from any other, similar platforming characters of the time. Sonic the Hedgehog’s emphasis on speed and timing made for a game that, above all else, stood out and quickly made a name for both Sega as a company and Sonic as a character. Sonic could jump on enemies like Mario, but his ability to blaze through levels was considered a nice alternative to Nintendo’s mascot. Combine that with excellent level design that focused on demonstrating the hedgehog’s abilities in interesting ways, and it was enough to carve a path for Sonic and create a brand new franchise that managed, for a brief time, to outshine Mario.

Sega followed the title up with Sonic the Hedgehog 2 just one year later. It expanded on the gameplay by giving players bigger levels, a new attack (the Spin Dash) and the ability to play as Sonic’s sidekick, Tails. Many considered it to be an improvement on an already proven formula, and it went on to continue to demonstrate the hedgehog’s ability to rival Mario. Sega later released Sonic the Hedgehog CD for the Sega CD, which featured a time travel system, allowing players to move between different time periods for each level. This, in turn, affected the design of the stages, and gave people a chance to replay levels for different results. It wasn’t as successful as the previous two titles, but it is considered by many to be one of the best in the series.

Then came Sonic the Hedgehog 3, which introduced another character, Knuckles the Echidna, and a whole host of new stages. Like the previous games, it was well-received, but its release was quickly overshadowed by the release of Sonic & Knuckles the same year. It introduced Knuckles as a playable character, and featured some new levels, but it was the cartridge’s ability to connect to Sonic 3 (and also Sonic 2) which set it apart from the previous titles.

While Sonic 3 and S&K were originally planned to be released as one game, attaching the carts together gave you Sonic 3 & Knuckles. This combined both games into one, and allowed you to play through all of Sonic 3 with his red rival. Sonic 2 worked similarly, letting you play through that game with Knuckles, giving players a reason to go back to the classic with some altered stages and new abilities. – Andrew Passafiume

The blue blur’s 3D evolution

For the Dreamcast, Sonic Team brought Sonic into the 3D realm with an ample supply of ambition. Sonic Adventure was a large, free-roaming 3D platformer in a similar vein to Super Mario 64 (of course) and featured several playable characters. What made the game really stand out was that each character had distinct play styles and objectives. Sonic had more traditional stages based on speed and acrobatics. Knuckles played the role of treasure hunter. Big the Cat… fished. The game featured a variety of large hub worlds separate from the action levels, featuring their own plot-related events. Adventure also introduced the Chao minigame, a sort of virtual pet that made use of the Dreamcast’s VMU memory card. Unfortunately, with the advent of 3D Sonic came a bevy of glitches, camera issues and superfluous world-building that worked more and more against the franchise as time went on.

For the Dreamcast, Sonic Team brought Sonic into the 3D realm with an ample supply of ambition. Sonic Adventure was a large, free-roaming 3D platformer in a similar vein to Super Mario 64 (of course) and featured several playable characters. What made the game really stand out was that each character had distinct play styles and objectives. Sonic had more traditional stages based on speed and acrobatics. Knuckles played the role of treasure hunter. Big the Cat… fished. The game featured a variety of large hub worlds separate from the action levels, featuring their own plot-related events. Adventure also introduced the Chao minigame, a sort of virtual pet that made use of the Dreamcast’s VMU memory card. Unfortunately, with the advent of 3D Sonic came a bevy of glitches, camera issues and superfluous world-building that worked more and more against the franchise as time went on.

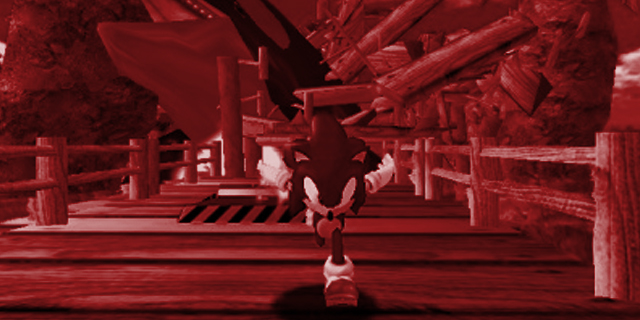

Problems notwithstanding, Sonic Adventure 2 was huge. The hook this time was the split between Hero Mode and villain-focused Dark Mode. Shadow the Hedgehog, Sonic’s infamous alter ego, joined the picture, and has been a major series staple ever since. The main mechanical addition was “grinding,” which came with some amusing product placement for now-defunct Soap shoes. Chao raising was also greatly expanded, almost becoming a game in and of itself.

Two years and a console generation later, Sonic Heroes arrived on the scene with a bizarre, albeit unique, gimmick. The game’s playable roster came in teams of three, with the player controlling all three members of a given team simultaneously, switching with the press of a button. Each team member had a unique power that was needed to pass various obstacles. Heroes had a generally mixed response, often praised for its visuals and sound design but criticized for having problematic controls, questionable voice acting and, again, camera troubles. – Lucas White

Defining an untethered Sonic

While Sonic Team continued to helm a console franchise that drove hardware throughout the Dreamcast era, handheld Sonic was out on its own a bit earlier, justifying an existence that didn’t push first-party technology. The decision was delayed, sure, by games like Pocket Adventure (NGPC) that simply remixed elements from the Genesis days. Ultimately, this duty fell to Dimps, a usually-behind-the-scenes studio that tended to work on secondary fare. With little pressure came the luxury of iterating only when necessary, so Dimps’ portable outings explored ideas within the confines of classic 2D gameplay.

While Sonic Team continued to helm a console franchise that drove hardware throughout the Dreamcast era, handheld Sonic was out on its own a bit earlier, justifying an existence that didn’t push first-party technology. The decision was delayed, sure, by games like Pocket Adventure (NGPC) that simply remixed elements from the Genesis days. Ultimately, this duty fell to Dimps, a usually-behind-the-scenes studio that tended to work on secondary fare. With little pressure came the luxury of iterating only when necessary, so Dimps’ portable outings explored ideas within the confines of classic 2D gameplay.

The three Sonic Advance games tried to incorporate more playable characters and aesthetics from the Adventure games, as well as the adorable-if-mostly-useless Chao. While Sonic Team tried to find the future of Sonic, Dimps reveled in the quirks of the past, with pseudo-3D special stages and even a Knuckles’ Chaotix-inspired partner element in Sonic Advance 3.

It was really this arm of the series that creatively carried the franchise in the DS era. Rush and Rush Adventure were generally lauded, while the console games were panned. It was time, then, for Dimps to pitch in on the other side. Sonic Unleashed‘s day levels, generally regarded as its redeeming half, were done by the studio, and these days Dimps works on Sonic the Hedgehog 4 episodes in addition to its 3DS duties. – Graham Russell

The once and future hedgehog

It’s an unenviable task to re-envision a series once defined by the need to justify blast processing or VMUs. It’s what Sonic Team had to do after the demise of the Dreamcast, and its failed attempts are notorious. Sonic the Hedgehog (2006) ultimately died by its rushed, buggy nature and strange, inconsistently-realistic setting. Sonic and the Secret Rings was regarded as less of a failure, but proved to distill the formula down just a bit too much, into something we’d now compare to a Temple Run-style mobile design.

It’s an unenviable task to re-envision a series once defined by the need to justify blast processing or VMUs. It’s what Sonic Team had to do after the demise of the Dreamcast, and its failed attempts are notorious. Sonic the Hedgehog (2006) ultimately died by its rushed, buggy nature and strange, inconsistently-realistic setting. Sonic and the Secret Rings was regarded as less of a failure, but proved to distill the formula down just a bit too much, into something we’d now compare to a Temple Run-style mobile design.

But Sonic Team wasn’t yet ready to give up on making Sonic into something new. Sonic Unleashed was a return to speed-based gameplay… except when it wasn’t. Sonic Team’s “were-hog” night levels were slow and plodding, and Sonic just isn’t supposed to be slow. You can imagine the developers sighing and saying “fine” in the next effort, Sonic Colors, which just built on those day levels for a full game. It was a quiet retreat from disaster.

It was only when Sonic Team embraced and even reveled in nostalgia when it seemed to recapture the enthusiasm of its fans. Sonic Generations brought back old levels and recent ones, redesigning them to be played in both 2D and 3D. It conveniently glossed over the franchise’s dark periods, and it’s probably best; it’s a feel-good adventure with lots of references and curtain calls.

With the recent partnership with Nintendo, it seems that Sonic‘s future will be building on the Colors legacy, with bright environments, kid-friendly worlds and designs that keep Sonic moving forward. – Graham Russell

What’s the peak of the Sonic the Hedgehog series?

Lucas: While I recognize the importance of Sonic to the 16-bit canon, I was never a huge fan of the series. I did, however, really dig Sonic Rush. It suffered a bit from “hold right to win” syndrome, focusing far more on speed than the clever level design of the past, but it had a lot of things that drew me in: a slick aesthetic, wacky music, very functional controls and, well, a great sense of crazy speed. The absence of most of the annoying side characters helped, too.

Lucas: While I recognize the importance of Sonic to the 16-bit canon, I was never a huge fan of the series. I did, however, really dig Sonic Rush. It suffered a bit from “hold right to win” syndrome, focusing far more on speed than the clever level design of the past, but it had a lot of things that drew me in: a slick aesthetic, wacky music, very functional controls and, well, a great sense of crazy speed. The absence of most of the annoying side characters helped, too.

Graham: As much as the series has found its footing as of late, it was at its best as the centerpiece of a console’s lineup. Sonic Adventure 2, with all its quirks and failings, was the last appearance of Sonic Team’s unique ambition, and the figurehead for the Dreamcast’s last gasp. Also, yeah, I like the Chao Garden a lot.

Graham: As much as the series has found its footing as of late, it was at its best as the centerpiece of a console’s lineup. Sonic Adventure 2, with all its quirks and failings, was the last appearance of Sonic Team’s unique ambition, and the figurehead for the Dreamcast’s last gasp. Also, yeah, I like the Chao Garden a lot.

Andrew: I can respect the 3D Sonic games from a distance, but despite my love for SA2’s Chao Garden, the 2D games were always the best examples of Sonic’s mechanics being used to their fullest potential in my mind. To me, Sonic & Knuckles is probably the peak of the franchise, as it acted as both an excellent stand-alone title and a game that connected to Sonic 2 and 3 in pretty cool ways. The decisions lead to the creation of Sonic & Knuckles don’t matter; it’s an excellent entry in the series that has yet to be topped, especially combined with Sonic 3.

Andrew: I can respect the 3D Sonic games from a distance, but despite my love for SA2’s Chao Garden, the 2D games were always the best examples of Sonic’s mechanics being used to their fullest potential in my mind. To me, Sonic & Knuckles is probably the peak of the franchise, as it acted as both an excellent stand-alone title and a game that connected to Sonic 2 and 3 in pretty cool ways. The decisions lead to the creation of Sonic & Knuckles don’t matter; it’s an excellent entry in the series that has yet to be topped, especially combined with Sonic 3.

In our next installment, we follow up Sonic with the plumber-shaped shadow he perpetually lives under: Mario. For more, check out the archive.