Have you ever considered that you have two social lives? The first is your real-life social experience, whether you are interacting with people in person or online. The other, however, is one not many people consider: your gaming social life. And I’m not talking about how you act when you get killed in a shooter or lose an intense match in a fighting game. I’m referring to how your personality is portrayed through a character in a game and how that character reacts to situations and other characters based on that personality.

Whether it is a character of your own creation or a character created by the developers, it’s very easy to get lost within the lives of these fictional people. With the continuing rise of player choice in games, we see it prevalent in a lot of genres, but the one that always comes back to it is the RPG.

RPGs are, by definition, a game in which you are playing the role of another character, even if that character was crafted by you. Yes, that’s the obvious part, but people sometimes overlook what makes this different, almost fictionalized social life you lead something special. When you’re playing a game, your character, whoever it may be, is ultimately making decisions based on your reactions, but are they really your reactions? Or are they simply how you think that character would react?

It’s so easy to get lost in certain games that you forget that maybe, just maybe, you would personally never do something that you have decided to make your main character do in a game. It’s what they would do and, in a way, it’s shaping their social experiences, not your own. If you decide to verbally attack this character’s friend instead of forgiving them for a mistake they made, it might not even be you making that choice; that’s you inside of the mind of the character you control. Sure, we shape these characters in one way or another, but eventually the characters become their own person and lead their own social life. At that point you have lost all control despite being the one in complete control.

There are two prime examples of this. The first is the player-created character. To look at a recent example, let’s talk about the Mass Effect trilogy. Shepard is, no matter the race or gender, almost predetermined in many ways. Everything that happens in the main plotline of those three games will happen regardless, and Shepard, despite the many choices players make, will still continue along that path. But what makes Mass Effect unique is how those scripted elements tie in with the choices you make along the way. Despite how you feel about Mass Effect 3’s ending, your Shepard is still your Shepard and, for many people, this character is entirely distinct from the person controlling them.

My Shepard was a renegade badass who cared about completing his mission no matter what. He was all about making sure those who got in his way were punished. He wasn’t without a heart; he still cared for the friends he made along the way, but ultimately he was focused on the mission more than anything. Despite that, Shepard still had time to interact with everyone aboard the Normandy, even if the conversations didn’t always end for the better.

This was Shepard, but this was not me. I would never make those choices, and I would always do what was right over anything else. In reality, I am a Paragon, but Shepard is as far away from that as possible. I could have made him like me, but I didn’t. Whether it was an experiment or the idea that I just wanted to separate myself from the character from the beginning, it happened and there was ultimately no turning back. To change who Shepard was halfway through Mass Effect 2 would essentially be re-writing his story.

Shepard’s social life was not particularly great, but he enjoyed his many conversations with Garrus, Tali, Liara and the rest of the Normandy’s crew throughout his many adventures across the galaxy. Shepard was a bastard, but that doesn’t mean he didn’t care. Because of this, Shepard became known as a hero and a true friend despite his ruthless behavior; part of this was already foretold by the writers at BioWare, but part of it was my own legacy. I was not Shepard, but when I controlled him, I stepped into another life, another version of myself, even if that version would never coincide with my real one.

As someone who loves to be engrossed in these fictional worlds, like Mass Effect’s, it can be very easy to see where the real me would stop being “in control” and the other me (Shepard, for example) would begin to take over. And this isn’t just about making the red choice or the blue choice, this is about Shepard and how he interacts with character as well as how others see him. To those who never experience this separation, I can’t even imagine it; it would be weird to see Shepard and myself almost in complete coexistence (besides the whole “save the galaxy” thing, of course).

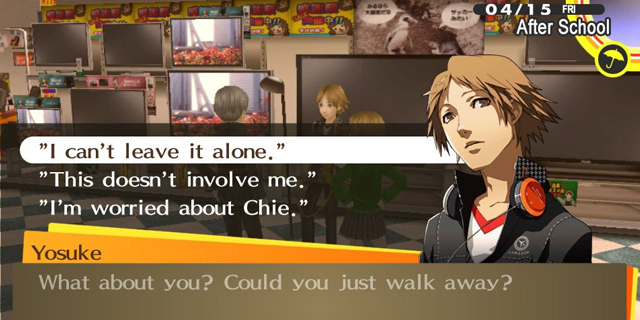

The second example, one that takes the idea of a “social life” inside of a game and applies it to the actual gameplay mechanics, is Persona 4. This is a more obvious example than what might be apparent in something like Mass Effect as you already have a pre-determined character that will, for the most part, live a pre-determined life. The idea that you, the player, are separate from the main character (MC) is pretty easy to comprehend, and most people who play Persona 4 will most likely have this idea in mind as they progress through the game.

MC is an ordinary high school student, and that alone might make the separation between the life of the player and the character very obvious, depending on the age of the person playing. That being said, the separation may not be as obvious a distinction as some think. This is a game all about the social experience, and not because it influences how other characters see you so much as it influences how you see the other characters. And since the social links, one of the game’s main hooks, play such a huge role in the gameplay mechanics, it’s not something someone can merely brush aside and forget about. This is something everyone playing Persona 4 will get to experience, but how much of it they experience is a different story entirely.

When the game begins, you might start off hating (or simply not understanding) this small group of teenagers. You could begin their social links as a gameplay necessity more so than a desire to interact with them, but the more you get to know them the more they grow on you as a player. There is the possibility they become less interesting to you as time goes on and social links develop, but you soon see the potential in continuing on the path for the purposes of the mechanics.

Whether or not you attach to these characters, they are a part of MC’s life, and he will always trust them and see them as his best friends. You might hate Yosuke, but find that his bond with the MC is as true as friendship gets, creating that separation yet again. This is a more linear approach to character development, as this cast will be the same characters whether or not your pursue their social link, but these social interactions serve the player more so than the character (and, by extension, the character’s social life).

The roles are essentially reversed. You can talk to Chie all you want, but she will still be the essentially the same Chie throughout the entirety of the game. But your perception of Chie will be different, even if the MC still sees her as one of his best friends regardless of what that perception is. You could respond to her as negatively or positively as you want, but it won’t matter to anyone but yourself. The benefits are seen mechanically, but not narratively, thus creating the separation between the player and the character.

You develop a second social life in Persona 4 for just that purpose: to develop your own personal connections with these characters regardless of what happens in the game’s main story. It’s a fascinating system full of small hooks to keep you playing and expanding on your own personal relationships with these otherwise fictional characters. There is still room in Persona 4 for character progression through the main story, but the majority of it happens in entirely optional content, but that content begins to seem more necessary the more you play. It’s an endless cycle that ultimately rewards the player on multiple levels for simply being able to care about these characters.

Both approaches are brilliant and offer many different possibilities for future RPGs. We’ve already continued to see the influence of Mass Effect’s choice system run through other games, and the potential to see the amazing social aspects in Persona 4 used in other games is still out there. They hook us with their base mechanics but draw us in by allowing us to establish new social lives outside of our own. All games can be used as a form of escapism, but the ones that truly succeed take full advantage of our second social lives, whether we realize it or not.